Looking back on my year abroad in Germany

One day during the pandemic, as I laid in bed burning with cabin fever, I thought, “I gotta get out of here.” My search for adventure led me to the Congress Bundestag Youth Exchange (CBYX). The scholarship program sends 250 American high school students to live in Germany and 250 German students to live in America. I applied expecting to spend my sophomore year living in a beautiful European city and taking the train to school everyday.

When I got my first email from my host parents beginning with “Greetings from Jübar” my first thought was, “where?” One of the biggest risks in going abroad with non-profit programs like CBYX is that you have no choice where you live in the country you are going to. Your application is sent out to host families all over the country and if they pick you then that is where you’re going. It turns out, the village of Jubar is home to 600 people right on the border of what used to be east Germany. There is no train station and no grocery store. There is an elementary school, a post office and fields as far as the eye can see. My friend Hannah joked that I had been placed in the Kansas of Germany.

My anxieties about living in what could not even be classified as a town were slowly soothed as I met the people who lived there. My host parents were a retired couple who couldn’t speak English, but patiently listened to my broken German. They invited me to share my culture and always tried to accommodate my wishes. I also met my friend Hannah, who lived on the opposite end of the village, which was a 15-minute walk away. Hannah was in my class at school and had learned English from American TV shows. She translated between my host parents in the beginning and became my closest confidant and friend.

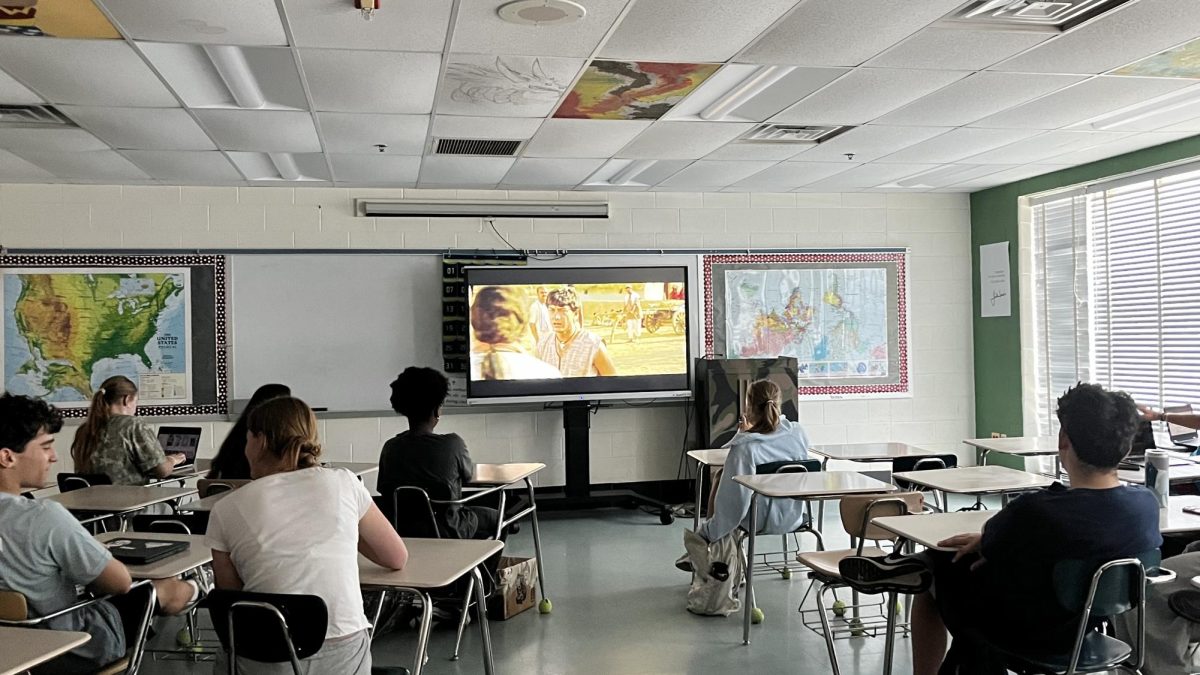

Needless to say, German school is vastly different from American school. After elementary school kids attend one of three types of high schools based on their academic level. I attended Beetzendorf Gymnasium in a nearby village. My school had 400 students and a herd of sheep behind our schoolyard. Most kids had never met an American. I was asked on my first day if I owned a gun and whether McDonald’s tastes different in Europe.

Air conditioning is also a rarity in many German buildings. Fresh air is valued and the windows are always open, even when it is snowing. Breaks in between classes can be half an hour long and everyone has to go outside. There is a German saying, “There is no bad weather, only bad clothing.” Teacher shortages in Germany also mean that if a teacher doesn’t show up, you often don’t have to go to class. There are no security guards, hall passes or locked doors. Students come and go as they please.

In general, kids are given much more freedom at much younger ages than in America. Informing your parents is more common than asking for permission. As long as I told my host parents where I was going, it was fine for me to go anywhere. The law permits teenagers above 16 to drink and to get their license to drive motorbikes. Teenagers drink with and around adults at so-called “village parties.” It’s not considered taboo at all. Hannah and I were even bartenders for one such village party. I found that German teenagers have a more healthy social life than American ones. Kids go watch a soccer game or drive their motorbikes together rather than staying home and doing homework because German schools rarely give out homework. The thought of doing schoolwork outside of school is silly.

This embodied the respect that Germans have for time. People’s time is much more respected. It’s why being late is rude and working overtime is uncommon. This culture of straightforwardness and efficiency is often mistaken as rude or harsh. Compared to Americans, Germans just say what they mean. When people ask you how you’re doing, they genuinely want to know.

Going on an exchange year is not for the faint of heart. It was difficult to adjust to a new culture and language without any of my friends or family. It wasn’t until December that I could carry out a decent conversation and only at the end did I feel truly comfortable communicating in German.

One of the hardest things about going abroad is that the minute you feel at home, it’s time to leave. Living in a tiny village might have been the best thing that could have happened to me. I found a tight-knit community that supported each other and me during a stressful time rather than a city full of people with whom I didn’t connect. Despite all of the challenges, it was the most rewarding experience of my life. I learned so much more than a language. I met people I would have never had the chance to before and built the confidence to put myself out there. Now that I’m back, I feel lucky to have had such a fulfilling experience and I can’t wait to go back to Germany one day.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Walter Johnson High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.