Silence. That’s the first thing that students notice when they walk into the music department office. While the halls outside echo with student musicians singing, playing instruments and talking, the small office nestled in the westernmost corner of the school gives off the aura of an artist’s sanctum rather than the control room of a highly coordinated and fine-tuned music department. But it makes sense: in a school of 3,000 students, there are only four music teachers: Michael Helgerman, Kelly Butler, Andrea Morris, and Christopher Kosmaceski. Managing classes from 20 to over 60 students takes a deft touch, especially when teaching a wide range of instruments, ensemble compositions and music styles.

While there are guidelines provided by the county on what to teach, much is left up to the instructor, and each class period has its own unique challenges. The techniques that might serve to instruct students on how to play a particular section of music often don’t translate across other pieces, instruments or class periods. As a result, every student quickly comes to see what is often opaque for those who simply pass by the music suite on their way to the cafeteria: the minute – but also sometimes massive – differences between from teacher to teacher that reflect not only the courses they teach but also their individual personalities.

“The teachers here, they’re all so intertwined and they have such different personalities. In every class, it’s a completely different environment and they’re all very welcoming,” senior Destini Haith said.

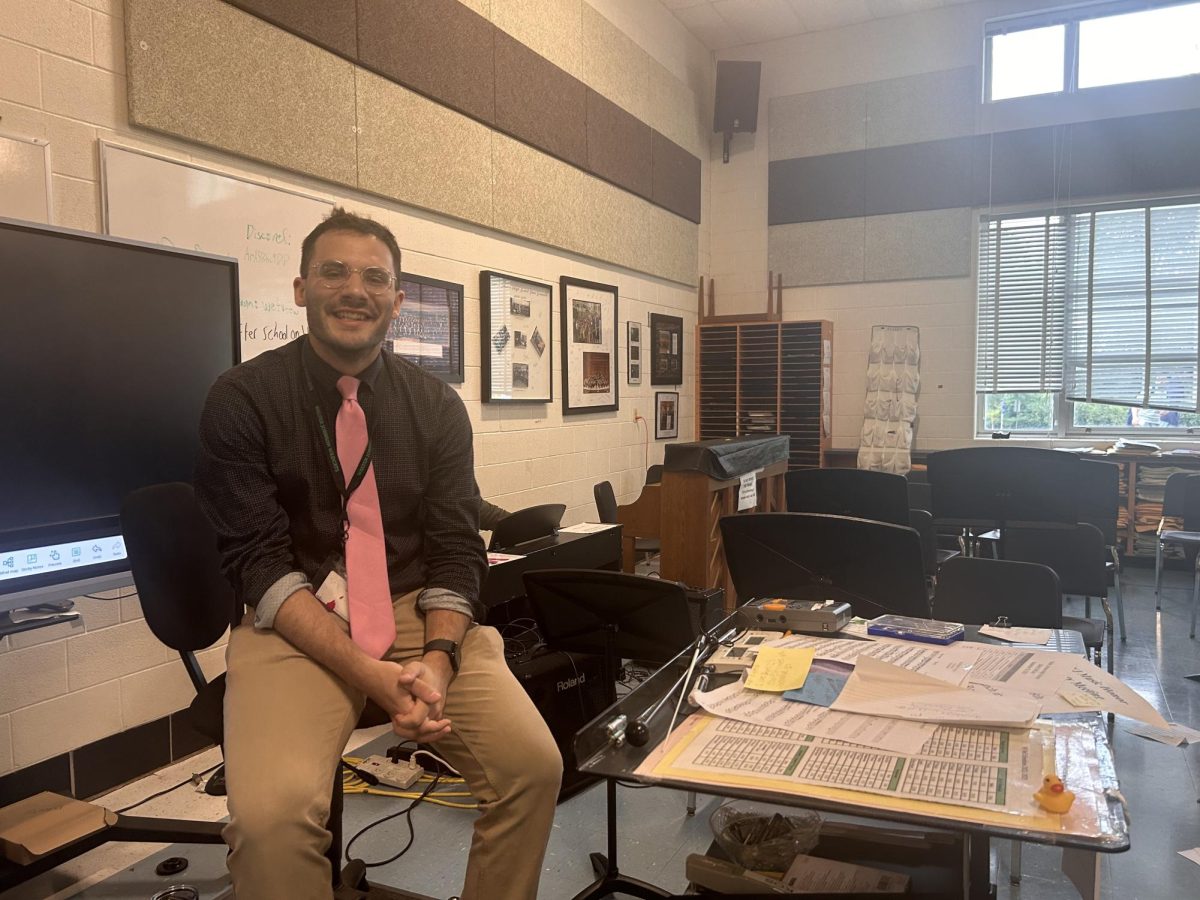

Helgerman:

The newest member of the department is Helgerman, a recent graduate from the University of Maryland who also worked as a former student teacher for music department head Christopher Kosmaceski. His methods for teaching Piano 1 and 2, Music Technology, Concert Band, and co-teaching Concert Orchestra rely on both seeing what connected with students which he learned in his time as a student teacher as well as his personality in the classroom.

“The way that a teacher presents themselves will absolutely affect the way that you feel about music,” Haith said.

Helgerman is known for the spontaneous enthusiasm that he brings to each of his classes and is unafraid to interject with words of encouragement. He also includes ways for students to utilize the skills that they’ve learned in the classroom in a broader day-to-day context

Nowhere is this more clearly evidenced than in Helgerman’s recurring Music Tech and Piano activity “Masterpiece Monday”, which is a way for students to connect what they are learning in class to the music they listen to every day. At the start of the class, he will play a song that some students may know. By the end of class, he will have connected an important piece of the song to the lesson they learned that day.

“One of my biggest goals is to develop literacy and appreciation for music, more so than being able to play the piano super well because no matter how much piano you’re playing after you take your piano class in high school, one skill that we can all develop that’s going to help us for the rest of our lives is the ability to listen to music more critically and better understand why you are reacting to the art the way you are reacting,” Helgerman said.

Butler:

Butler, the teacher for all four choir classes (General Choir, Show Choir, Advanced Choir and Madrigals) and co-teaching Concert Orchestra, had a similar opinion.

“What matters the most to me is that they don’t have to necessarily be a performer their whole life but that they appreciate and hear music in a different way,” Butler said.

Nonetheless, performance is at the core of all of the chorus classes. Butler holds the balancing act of constantly checking on each person individually and moving the class forward as a whole.

Butler splits the class into sections based on their voice parts, soprano, alto, tenor and bass. These sections comprise each choir and the group’s sound as a whole. In order to manage each section, she chooses section leaders who work with just their voice part on each song.

“It doesn’t feel like you’re ever being assessed and when you are being assessed … We know about them well in advance, we work with other people, we work with the teacher on it,” junior Sawyer Chism, a student in Guitar 1 and Madrigals (a chorus class), said.

Morris:

Morris teaches Guitar 1 and 2 and AP Music Theory and teaches a class of Piano 1. Both of these classes offer a vastly different learning experience compared to the more traditional music ensembles. Guitar 1 is much more open and self-paced, and students often have time during class to go out into the halls and courtyards and practice by themselves. Often Morris needs to listen to the entire class play a scale at once in order to determine whether the students need more practice. To assist students, Morris utilizes student aids, or DHs, to work with students one on one, allowing her more flexibility when she teaches in the classroom. AP Music Theory is where students learn to understand music on a more fundamental level. Though they don’t focus on a particular instrument, there’s more to the class than just sheet music. They analyze chords, melodies and chord progressions from both modern music and pieces from centuries ago.

“In chorus and band classes, the goal is performance, in music tech and music theory there’s not a concert we’re preparing for. It’s music but it’s also problem-solving, how to practice and how to get good at something that you can’t see,” Morris said.

Classes such as Guitar and Music Theory rely on the proficiency of each student versus the sound of a whole choir or orchestra. Oftentimes, Morris has the entire class play a section at the same time, which allows her to pick out individual areas that need improvement, as well as students who are performing exceptionally well.

“The closest thing would be if PE had everyone shoot a foul shot at the same time, you could see who missed,” Morris said.

Kosmaceski:

Ultimately, music class is not just about learning the music in front of you as it is about getting comfortable with the instrument in your hands.

“You have to practice the music, but you also have to practice the instrument,” Kosmaceski, the longest-tenured music teacher with nearly two decades of experience at WJ, said.

Kosmaceski leads the majority of the instrumental ensemble classes, including Wind Ensemble, Symphonic Orchestra, Symphonic Band and Jazz Ensemble. In his classes, Kosmaceski emphasizes the unique duty of ensembles to not just play their instrument during practice, but to listen to those around them as well.

“A rehearsal is not just an opportunity for you to learn your part, it’s to learn everyone else’s part, and how your part fits in,” Kosmaceski said.

Playing in an orchestra or ensemble provides the challenge of building a uniform sound, while also expressing creativity through your instrument. Kosmaceski will typically dedicate the first 10 minutes of class for students to tune their instruments and practice any music, scales or measures that they are having difficulty with, but after this first period, he keeps things focused solely on the wider sound of the orchestra as a whole.

One of the most unique challenges that Kosmaceski faces comes in the Jazz Ensemble class, where students may be tasked with performing an improvisational solo as a part of a piece. He recognizes that teaching creativity in music and the arts is a difficult, if not impossible, task, but believes that there are still meaningful ways in which he can help direct their creative talents.

One of Kosmaceski’s most well-known attributes is his knack for explaining musical concepts with analogies to real-life stories or food analogies to illustrate abstract concepts that may be harder to understand. Even students who have graduated years prior can recall terms such as ‘the jelly in the donut’, an enduring reference to the intrinsic importance of a part of a particular section of music that holds many of the same responsibilities to the sound as a whole as a jelly does in a jelly donut.

“Music is invisible, we’re teaching something you can’t see. Each of us has a unique style [and are] able to generate and discuss and perform and model and explain how to generate this sound that you cannot see,” Kosmaceski said.

The unique perspectives and methods that each teacher utilizes stem not just from the teacher themselves, but from what class they are teaching. In the moments when the classes reach their peaks of performance, it is as a result of the teachers and the students working together, using sticks, metal and string to convey emotion, beauty and language.

“You can either listen to the music or be the music,” Kosmaceski said.