On Wednesday March 23, the SAT test was held at WJ. If you happened to talk to any 11th graders about taking the test beforehand, you probably heard some rendition of the following complaint: “I can’t believe all of my teachers are giving me so much work right before the SATs.”

Indeed, it did certainly seem like no teachers were taking any consideration whatsoever for the stress students were under that week. Homework was assigned for Thursday. Tests were scheduled for Tuesday. Little time was designated for students to study or mentally prepare.

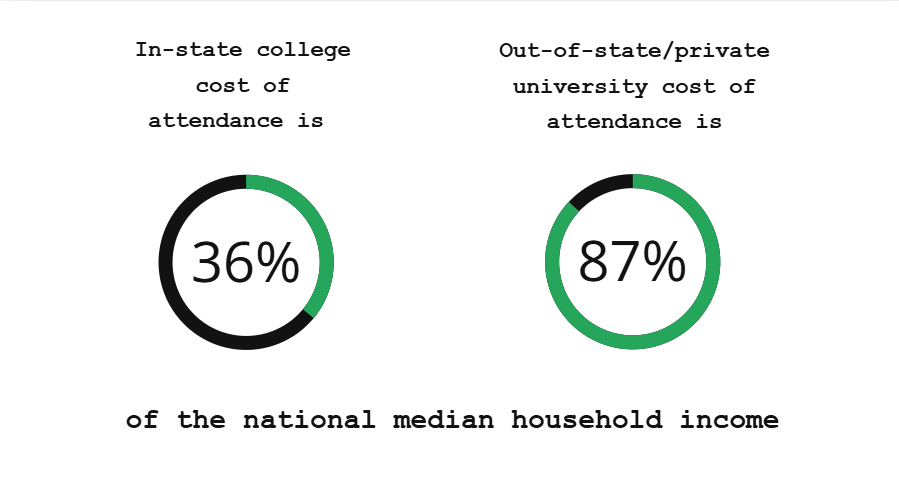

Despite many colleges and universities moving to “test optional,” make no mistake: standardized tests still play a considerable role in determining students’ admissions chances. Few such institutions would deny that they prefer a student with an SAT score than a comparable student without one. So, at such a critical moment in the school year, why did teachers not act to put their students in an optimal position to succeed on the test?

The fact of the matter is that this debate goes far beyond simply the SAT and the particulars of that specific day. Rather, the real question is: what obligation, if any, do teachers have to respect the extracurricular activities of their students? And should they be working to accommodate them?

The amount of time that students put into commitments outside of school can vary greatly. Something like an honor society or interest-based club might meet once during lunch at most once or twice a month, while many sports or highly demanding competitive clubs may require multiple hours of work outside of school a week. A job or internship may add on a higher level of stress and responsibility, especially if a family is dependent on that source of income.

Compounding all of these stressors, many of which are caused by an incessant fear of having enough activities to put on college applications, is the towering stack of homework assigned by teachers each night. In these assignments, students have a serious conflict: they’re only worth practice/preparation points which in most cases are barely enough to shift a student’s grade by .1%. But, at the same time they’re often key to keeping up with content that sometimes is not even covered in class.

Granted, a large portion of a student’s schedule is decided by that student, but strict credit requirements can often push a student to enroll in a class they might not otherwise take. Besides, it’s hard to predict what a work/life balance will look like a year from actually experiencing it.

The public school curriculum is inherently adverse to individual accommodation, which makes the ultimate choice a very difficult one for teachers to decide. Often, it comes down to the individual decision by a teacher or a course team to cancel a homework assignment, delay a lab due date or push back a test.

It must be kept in mind that the student, in desiring this brief respite from break, must keep their part of the bargain. They should be expected to act courteously to their teacher, complete all necessary work in a timely manner, and respect that it may not be possible to make accommodations in some circumstances.

However, the fact remains that the institution of school must coexist with the other responsibilities of a student’s life. To ignore such factors would undermine the individuality and complexity of each student and teach to an idealized student body, rather than the one that actually exists.

The MCPS Code of Conduct states that “staff will create positive, supportive, safe, and welcoming school environments, for all students and adults, that are conducive to teaching and learning.” Through recognizing the complex responsibilities of their students, teachers can fulfill the mission of public schooling to prepare every child for success.