“Mental health” is a term most commonly used to refer to one’s mental state of being and a sensitive subject of conversation in society. More and more people have started to discuss this topic, attempting to break down that wall and normalize talking about mental health and mental illnesses.

Even with this being a topic of conversation for many, the stigma surrounding mental illnesses or “bad mental health,” persists. “Bad mental health” is subjective and mental illnesses do not define an individual or their values.

“I think people get the wrong idea about mental health…mental health is different for everyone,” junior Fiona Ugarte said.

The most commonly known mental illnesses include depression, OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder), schizophrenia, anxiety, PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder), ADHD or ADD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and attention deficit disorder) and bipolar disorder.

Stereotypes and stigmas still surround these illnesses, even with efforts from the community to expand the conversation on mental health. Individuals with depression are called lazy, or worse, have their mental illness minimized by those who call themselves “depressed” at any minor inconvenience. People with ADHD or ADD get told they need to “calm down”, and those who have OCD compulsions get told that they are doing it (engaging in or performing these compulsions) for attention or for dramatics.

This type of behavior and mindset continues for just about every mental illness imaginable. While to some it may seem normal, to those who actually have these mental illnesses, these types of actions can be demeaning.

“Because of the stigmas that surround mental health and mental illnesses, it definitely prevents the people from wanting to talk about it. Because the people that they might want to talk to have those expectations of what that looks like in their head and might treat them differently because they disclose that they have x, y and z,” sophomore Ryan Autenrieth said.

These pre-misconceptions of others that individuals develop can influence the way they view them, and oftentimes, the way they treat them.

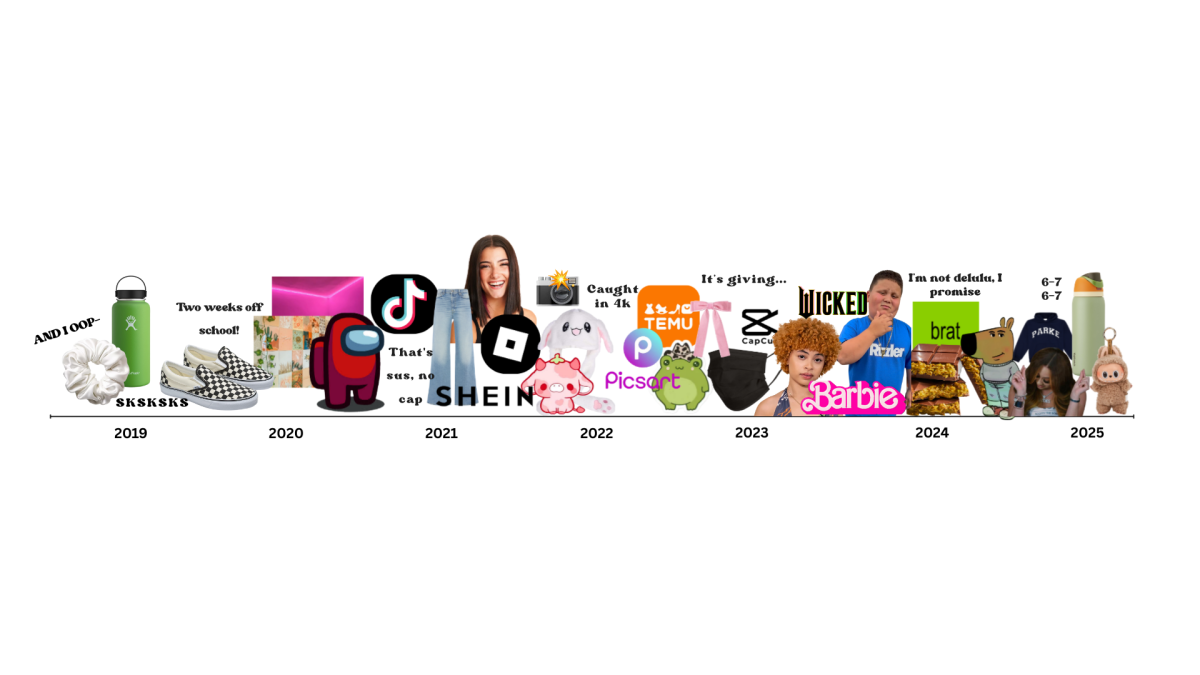

An aspect of mental health that isn’t talked about as much is self diagnosing. We live in a society where mental illnesses are romanticized, primarily by celebrities or influencers. They present parts of their mental illnesses, whether these illnesses are self diagnosed or not, in a way that makes it seem cool or trendy. The lifestyle these people lead is seen as directly linked to mental illness.

Depression? No, you are a melancholy poet in the 1900s. Have OCD? No, you are living in a clean and organized rooftop apartment in New York. Have ADHD? No, you live life to the fullest and are always laughing.

“You definitely see a problem with romanticizing it [mental health]… you know, you like having ADHD when it’s your ‘manic pixie dream girl’ thing,” freshman Riley Birdsong said.

These are just to name a few ways these illnesses are romanticized. In reality, these mental illnesses are so much more than the seemingly “positive” sides of them; when they are depicted in this way by celebrities they are practically being marketed for public appeal.

This has “encouraged” people to start self diagnosing themselves, to the point where those who really do need treatment don’t receive it or aren’t believed.

“I think there’s some people who maybe don’t have a mental illness but will pretend that they do, for the social… We live in a society that basically promotes depression,” senior Andres Zalowitz said.

This mindset also manifests through the way individuals present themselves. They have an idea or a stereotype of what a person with a certain mental illness looks like, and portray themselves in that way.

Depressed people don’t shower; people with OCD are orderly and neat; people with schizophrenia are twitchy and alert, and so on.

These stereotypes are also portrayed by their treatment of those with mental illnesses.

“There are almost expectations set, like if you aren’t ‘depressed enough’ to the point of crying every day, it’s not valid. So then it almost feels like a pressure that you can’t talk about it because it’s so different than what the ‘norms’ people have are,” Autenrieth said.

The idea of mental illness is romanticized to the point where people only have a vague idea, if any, of what a specific illness looks like; when those around them show real signs of a mental illness they are called over dramatic or “crazy” because these illnesses have been minimized to niches.

“A lot of people sometimes support mental illness, I mean support the people, until the people actually show signs of the mental illness… and I think you see on social media people just romanticizing or just ‘liking’ the mental illnesses… [they] seem to “cringify” depression, and it feels like you can’t talk about it,” freshman Oksana Borobiova said.

Students like Borobiova and Ugarte believe it is crucial to de-stigmatize and de-romanticise mental health, as well as change the narrative surrounding it.