INTRO:

The horizon of the Pacific Ocean was visible from the street corner as he set out in the morning to deliver the neighborhood newspapers. The beauty of the seascape contrasted the bitter headlines that filled the stacks of papers stuffed into his bag, ones that called his neighborhood the slum. Harvard Graduate and California native, Oscar Ramos, WJ’s AP Gov, US History and Latin American studies teacher is no stranger to overcoming obstacles. Using his own experience to guide him, he has devoted his career to helping immigrant and first-generation American students achieve greatness.

EARLY LIFE:

Ramos grew up by the oceanfront in San Diego in a barrio called Barrio Posole, composed of an extremely diverse community of Latinos, African Americans, whites, and Samoans. He recalls how strange it was to reside in such a rough area while being less than a mile from the gorgeous San Diego beach.

“[Barrio Posole] was the ghetto and it was a dangerous place. There were several gangs back then,” Ramos said.

Ramos describes Barrio Posole as an immigrant neighborhood of people who were struggling to make it in the United States. When recalling his education, he explained that there was opportunity within the schools, but it was still dangerous at home nevertheless. Because of this experience, Ramos feels like he can relate and hone in on students who are growing up with similar experiences.

“That’s where the pride in what I do comes from. The students who come from an immigrant background and those who struggle to make life in the United States,” Ramos said.

Ramos revealed that an inspiration behind his success is his older brother, Faustino. His brother was the first to go to college in his family and Ramos jokingly admitted Faustino was the “golden child” of the family. Ramos lightheartedly recalled the time his mother told one of her clients Faustino was going to Harvard.

“My mother was so spoiled by having her first child go to Harvard. My parents had no idea how hard it was to get in. My mother has always been a housekeeper and cleaned houses in a wealthy part of town. When she went to one lady’s house, the lady asked my mom if [Faustino] was going to school next year. My mom said, “Ah si, he’s going to Harvard.” The lady was like “What?” My mom said “Harvard.” The lady said “Harvard?” My mom said “Yea.” The lady freaked out! She couldn’t believe it,” Ramos said.

When you first walk into his parent’s house, the first thing you see is a wall filled with degrees and various awards. Because of Faustino’s success, people expected Ramos to be successful early on, fueling him even more.

“Being a competitive younger brother, I was like, ‘Well if he went to Harvard so could I.’” But for each school I attended, I was always in the shadows. Everyone was like “Oh you’re Faustino‘s brother. I was a star student as well with good grades and SATs, music, journalism and all that stuff,” Ramos said.

High school proved difficult, as Ramos felt a sense of confusion with his identity and his studies. He was immersed in various honors classes, but this made him feel even more alienated.

“My best friend in my neighborhood was in those classes at first with me, but he didn’t stay until the end. By the time I graduated high school, there was no one else in my neighborhood that graduated with me or in that track,” Ramos said.

He recalls how people would make assumptions about him because he wouldn’t use elements of Spanish in his English and vice versa.

“They assumed that I was embarrassed to be Mexican. my parents didn’t speak English and they drilled into me that you speak English or you speak Spanish. Don’t mix them up. For them it was a sign of lack of education,” Ramos said.

He revealed how his academic life and his home life were two completely different worlds, which exacerbated his feelings of isolation.

“When I went home there was a disconnect because my dad didn’t go to school at all and my mom only went through middle school. It’s not like I had academic conversations at home,” Ramos said.

Despite this sense of isolation and disconnect, he applied and was accepted to Harvard University.

HARVARD:

Boston felt like a completely different world.

“I felt like an imposter,” Ramos said.

Growing up, he would sometimes accompany his mother as she cleaned lavish homes in California, but Boston held an unimaginable level of wealth and privilege.

“The student culture there was extremely different,” Ramos said.

He recalls spending freshman-year Thanksgiving with his native Bostonian roommate and his family,

“I couldn’t afford to go home [for Thanksgiving]. His parents are educated and they were sitting around the dinner table, and his mom is talking about the documentary that she saw and the dad’s talking about the museum that he went to. I was almost panicked because I thought home was a sanctuary where you didn’t talk about academics. It was a weird shift,” Ramos said.

By the end of his freshman year, he had found a community of first-generation American students like him. They found comfort in the knowledge that they were enduring the same experiences.

“We were all struggling with the feeling that Harvard isn’t made for poor people. Can you get that message in a million different ways? Even down to the aspirations that we had,” Ramos said.

He knew he wanted to be a teacher from a young age, but countless people at Harvard urged him to go into a higher paying job such as a lawyer or banker.

“I’m proud of my career, but there was a constant reminder that this place [Harvard] didn’t have you in mind. They let a few of us in because they want to show us on the pamphlets. I’m fortunate that I’ve been able to use a degree that I got there to open doors to the career that I have. I’m glad I didn’t let them convince me otherwise,” Ramos said.

He always hated the idea of having a set life course and shortly after graduating from Harvard, he took a chance and ventured abroad. Ramos felt like he was in a “rat race”, like several of his friends at Harvard who were working on Wall Street and in high prestige firms and he knew he had to get away and live. His degree was in Latin-American studies, so he applied to teaching jobs all over Latin America, as well as other countries all over the world.

“I knew I didn’t care where I went, but whoever offered me a job first is where I was gonna go. Within a week, I had a job offer from a school in Morocco. I had no idea what was waiting for me out there, but that was kind of the point,” Ramos said.

He felt that Morocco provided him with far more life experience than Harvard did, as he arrived there at 22 and left when he was 25, traveling and living a life of adventure.

THE MORROCAN EXPERIENCE:

He arrived in Morocco one week before 9/11, and he recalls how this outsider view of one of the darkest days in American history made him rethink his own identity.

“Being abroad during the war on terror and seeing the United States from the outside made me think more about my American identity. I had a sense of disgust and pride in the United States at the same time. Disgusted of what we’ve done to countries, and pride in the good we’ve accomplished,” Ramos said.

The experience gave him a stronger appreciation of the promise of the US, as he thought back to his parent’s journey to the US.

“There is no country in Latin America where immigrants from another country could go there illegally and their kids would benefit from the resources of that country to the point where they could go to Harvard,” Ramos said.

On top of this, Morocco provided him with a unique experience: the ability to blend in. Ramos shared how in the US, he stands out depending on where he is if there aren’t various other Latinxs around.

“It was different to be brown in a country full of brown people. In Morocco, if I wore a hat and they didn’t see my hair, they would assume I was Moroccan. It was so neat to be in a place where I didn’t have to feel the legacy of American racism and not have that be part of my daily experience,” Ramos said.

He stayed in Morocco for four years, teaching on the weekdays and traveling on the weekends. He enjoyed the experience, but he knew he had to return to America.

“I felt a sense of responsibility to my own community and other people who are like me. Not just Mexican immigrants, but anyone else who’ve had similar experiences. My parents didn’t go through all of that for me to be one of the few people plucked out of the Barrio, go to Harvard and live this fancy life in Morocco going to parties. I felt that tug of going home,” Ramos said.

After four years abroad, he returned to the US.

BACK IN THE STATES:

When he got back to San Diego, Ramos got a job teaching AP Government and AP European History at the Preuss School UCSD, a charter school on the campus of UC San Diego made up of low-income students that would be the first in their families to go to college. The school provides rigorous classes that prepare them for college.

“I’m a big fan of Pruess and I love to spread the message of giving rigorous college-prep education for low-income students. I think we need to do a better job with that,” Ramos said.

He recalls how close-knit the school was, with only 100 kids in the graduating class. Ramos says that the foundation of a close school community such as Pruess is teachers who care about kids, administration who cares about teachers and supportive parents.

“It’s not an exaggeration to say that the school was a family, It was cool how everything fell into place,” Ramos said.

Additionally, Ramos recalled coming back to the US from Morocco as a rocky transition. He had experienced a lifetime of new things and had a completely different mindset, so he found maintaining friendships to be quite difficult. He laughed when remembering re-connecting with one of his former students from Pruess several years later. She told him that when he first shared these feelings of isolation due to his experiences, she thought he was elitist. She went to college on the East Coast and realized she identified with the exact feeling of alienation that Ramos experienced.

“It’s hard to be a person of color who is educated and came from a poor background and be able to truly understand all of those things. It’s a balance where you feel like you just can’t talk about certain things in front of certain people. I don’t make many new friends for that reason. It is still hard to make connections,” Ramos said.

Ramos met his wife while teaching in Morocco and she happened to be from the Bethesda area. After their son was born, his wife was teaching at Montgomery College and he was still teaching in California at Pruess, so they would fly back and forth on the weekends to see each other and their son.

“I would fly Friday night, get to Maryland on Saturday morning, spend Saturday and Sunday, fly back Sunday night walking to the house around midnight and then teach on Monday mornings. It was crazy.” Ramos said.

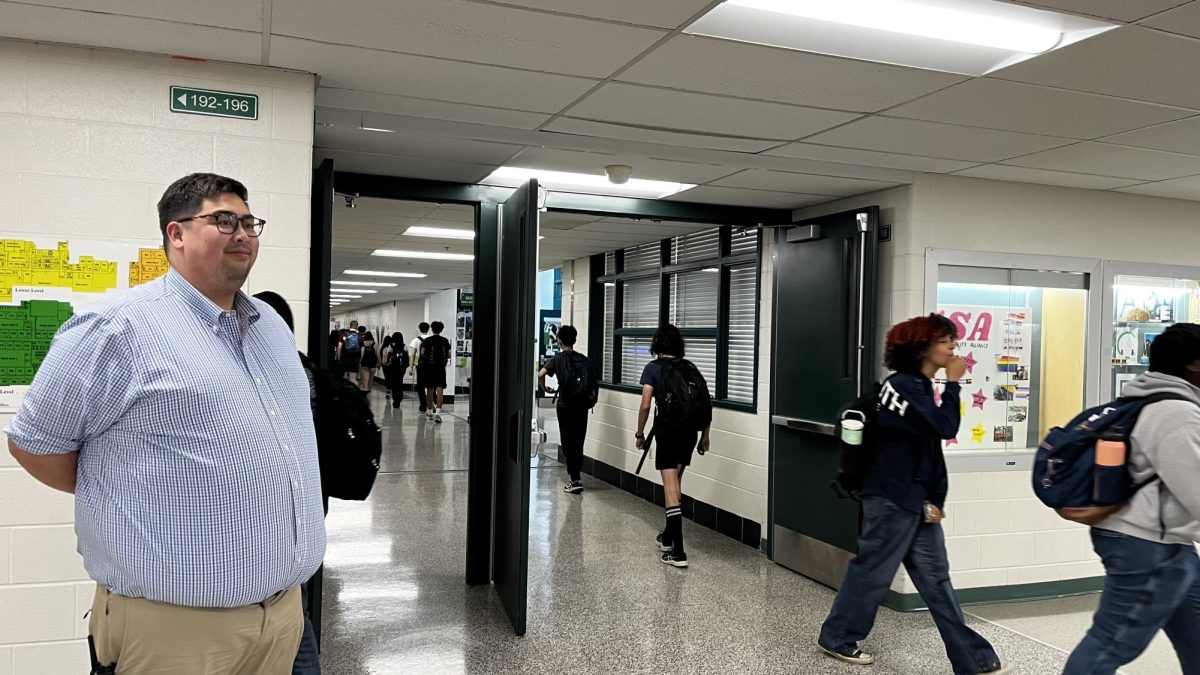

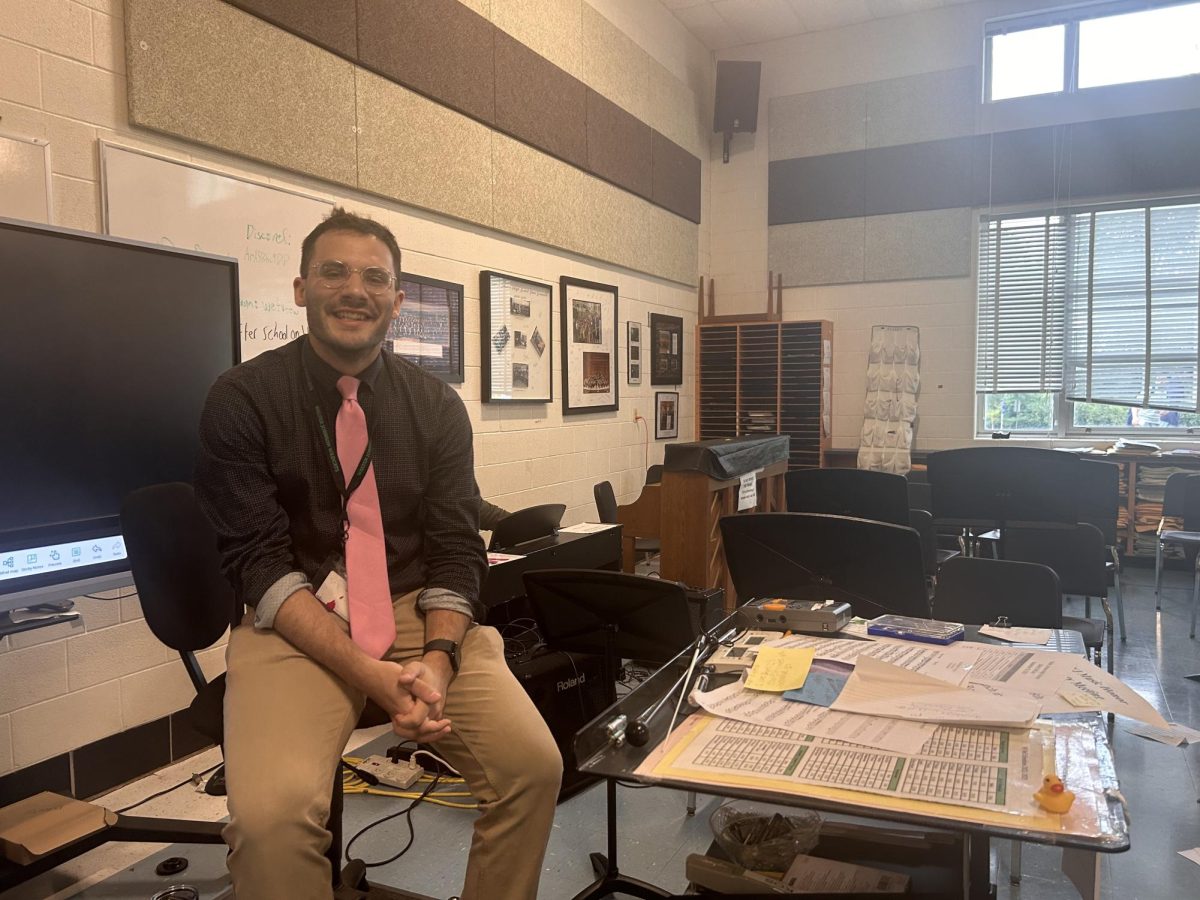

Eventually, he knew he had to move to Bethesda permanently, so he packed his bags and headed across the country. When he first got there, he worked at a middle school in Olney but knew that was not his age group. When he applied to high school positions, the final decision came down to BCC and WJ, and he ultimately chose our school.

“Again, I’m extremely passionate about helping low-income minority students and while neither school has a student body overwhelmingly like that, this school was the best fit,” Ramos said.

He started teaching here in 2019 and has since continued helping students with their goals and paths ever since.

IMPACT AT WJ:

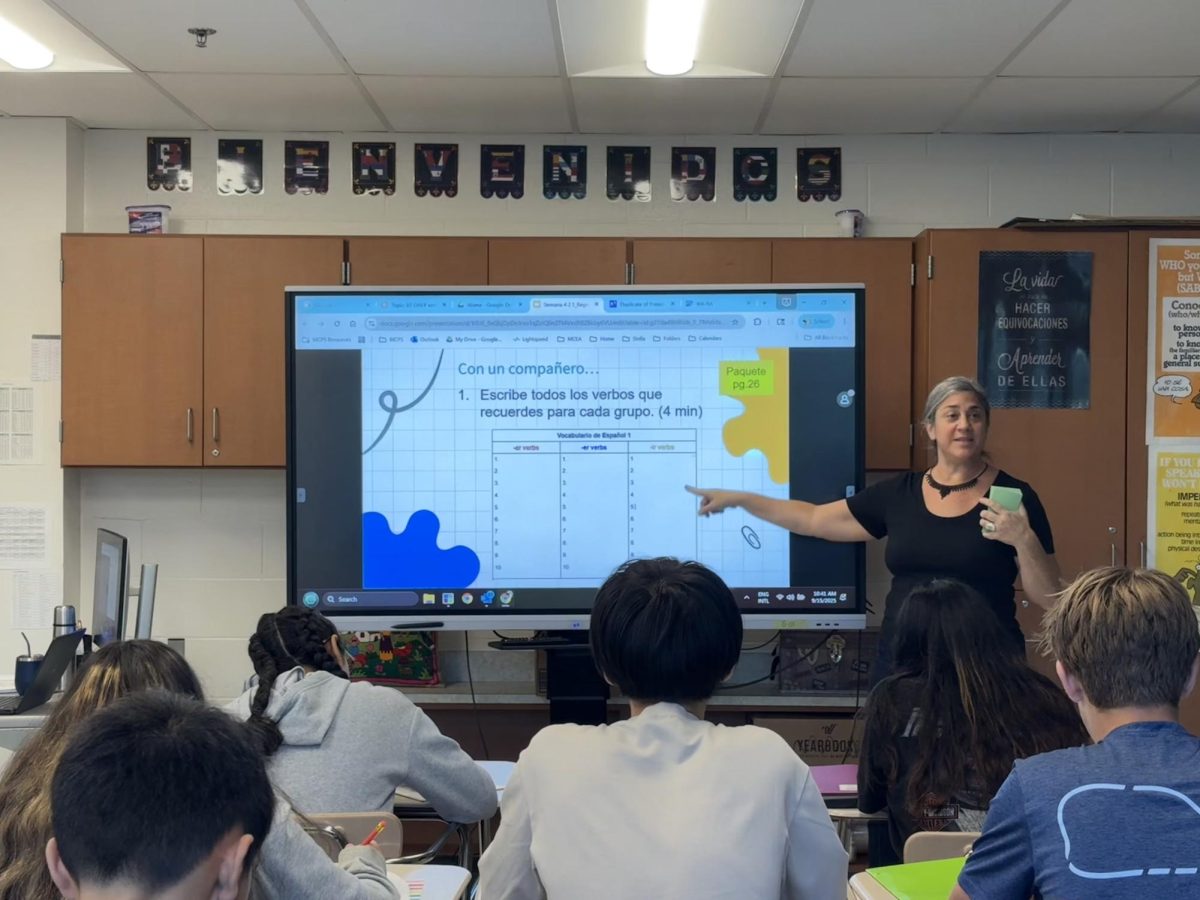

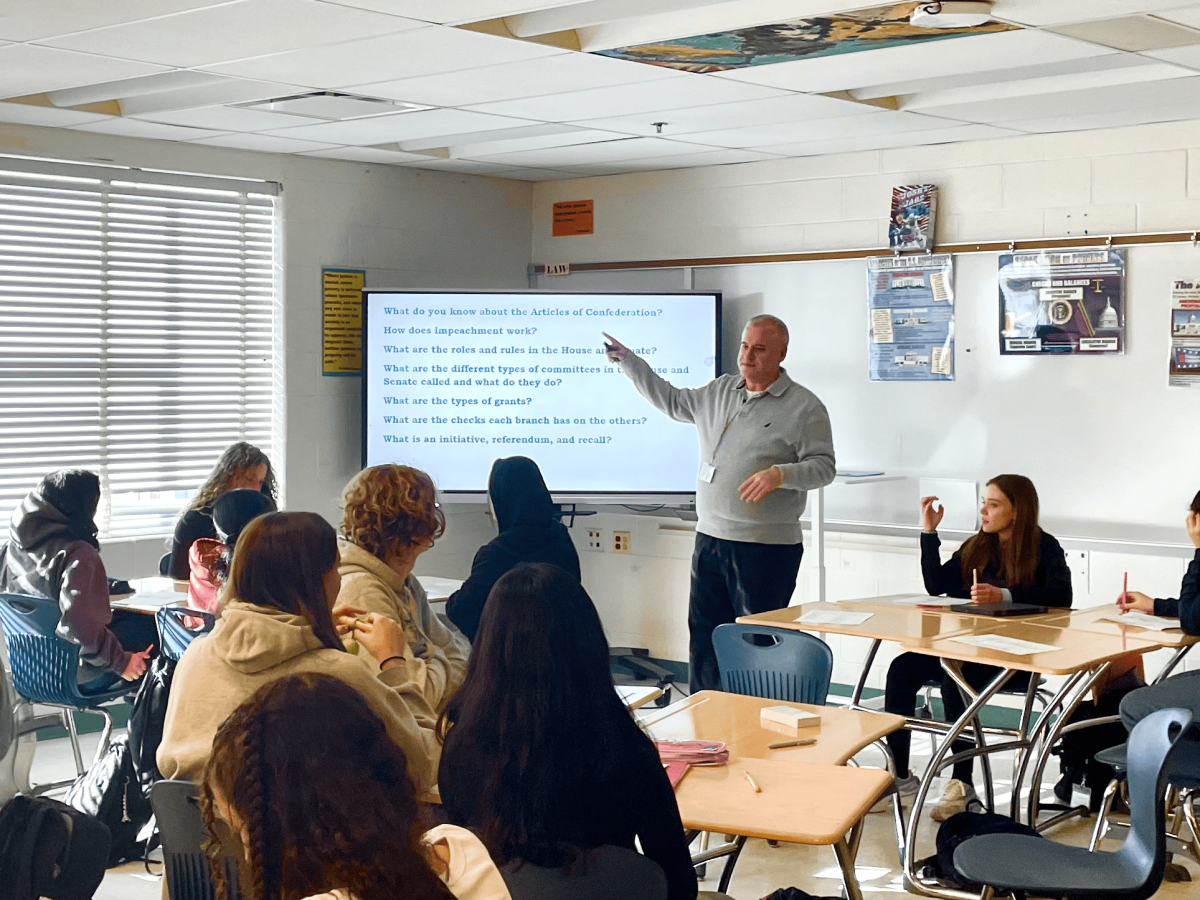

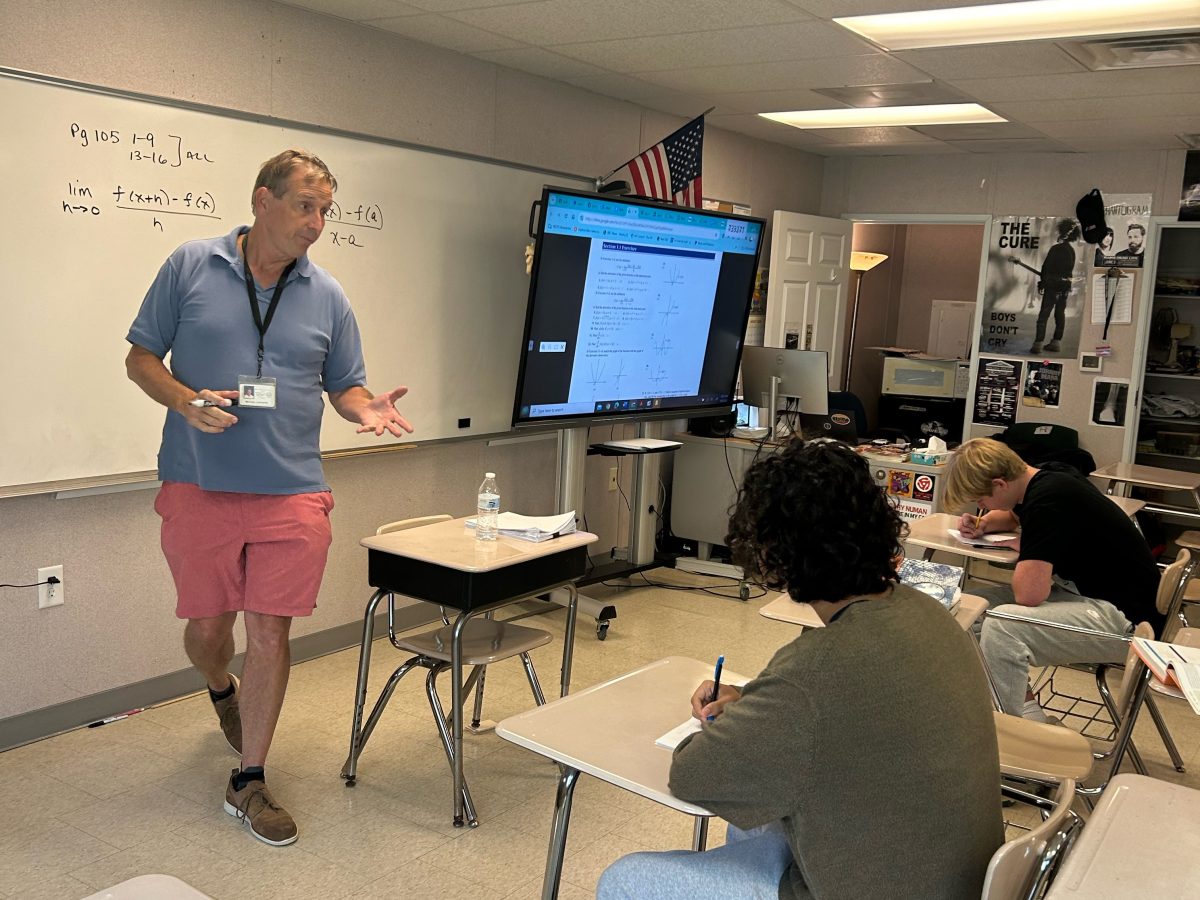

Ramos’ teaching style is highly regarded by his students. “Even with a switch to online learning he was still super engaging and you could tell he truly cared about his students. When we were in person, he engaged all the students and gave interactive lectures,” sophomore Juliana Romeros said.

He spends time creating interactive slides in a lecture-style instruction that students find to be incredibly helpful. Sophomore Daniela Salas shared that Ramos’ teaching style worked perfectly for her.

“I can’t learn off of notes and Mr. Ramos taught interactively, which was amazing. When I was taking a test it was easier to remember different things. I definitely think that having him as a teacher helped me so much,” Salas said.

Many students feel Ramos offers a refreshing teaching style that inspires his students to dig deeper when studying Latin American studies, US history and US government through his interactive lecture style.

There is a noticeable lack of POC teachers at our school or in MCPS. According to MCPS data, as of 2018, 72.7% of the teachers in MCPS schools were white.

“I don’t think our school purposely doesn’t hire teachers of color, but I feel like they should put out more information for POC to become teachers and make a more accepting community,” Salas said.

Salas is Mexican-American and remembers how comforting it was to see a fellow Mexican and POC at the front of the classroom.

“He is the first Hispanic/Latinx teacher I’ve had, and I definitely felt more included and accepted in the classroom,” Salas said.

Romeros, along with several other students feels the same way.

“You want the students to feel comfortable. If you have such a diverse school you should try to hire diverse teachers. There needs to be a new wave of Teachers,” Romero said.

Recent MCPS data has shown an increase in POC teachers, and several students Ramos is a shining example of why having teachers of color is so important to creating a welcoming school environment.

This Californian, First Generation American, Harvard graduate serves as a beacon of light for students struggling with their own identity, future paths and those looking for inspiration. There is no doubt that the school has struck gold with its newest history teacher, as Ramos continues to teach, inspire and help all his students achieve greatness.

Hannah Sollo • Apr 19, 2021 at 9:25 am

I had Mr. Ramos last year for US History! He was a great teacher; a breath of fresh air.