There’s a singer named Fujii Kaze who’s gained popularity in the past year. He’s a talented musician with that classic Japanese vocal tone — careless, whimsical and absolutely freeing. His music is opium for someone like me who grew up consuming music and media from all sorts of cultures and backgrounds, including the land of the rising sun. He performs a variety of different genres from gospel to rock, jazz, R&B and ballads, and has quickly become one of my favorite artists to listen to, regardless of the time of day and my current mood. Of course, like most other people, I’d love to share his music with my friends and peers, yet I always seem to stop myself before I do.

“Oh, they probably don’t even like this type of music,” is what I tell myself as I hold down the backspace button on my phone mid-text. It’s a habit that formed early in middle school when I became wary of openly displaying Asian culture with all of the disparaging remarks and adverse reactions I got from classmates with whom I attempted to share it. Before then, I never considered the shows and music I grew up with would be considered queer, but the culture shock proved otherwise. I hadn’t even noticed until freshman year that I’d phased anime, manga and Asian music out of my life in the effort to keep up with the status quo.

I bring this up because, in light of these past few years, I feel that I and many other Asian American teens have become more cognizant of how we’re perceived in America. From the continued perversion of Asian men and women, the conversations surrounding how being Asian plays into the education system and future workplace, the lack of representation in American culture, to of course, COVID-19 and how it’s affected the treatment of Asian Americans and Asian immigrants alike, I can’t help but feel misrepresented and left behind in a supposed era of progress.

To be Asian in America:

Every group, be it based on race, gender, culture or interests, has to deal with preconceived notions and stereotypes. Evidently, some prove to be more harmful, while others operate under the guise of “positive reinforcement.” Being an Asian male, I think many of my fellow yellow brothers can immediately come up with a few stereotypes that affect us on a regular basis: we’re born unathletic and lacking in desirable masculine qualities, but at least we have the brains to try and make up for it. Asian women, on the other hand, face remarks of being petite and demure and have become subject to sexual fetishization. In addition to this, when Asian women are met with regular disgusting remarks regarding their beauty, they’re told that they’re only attractive because they must’ve had cosmetic surgery. These stereotypes are only the tip of the iceberg, considering how vast and diverse the continent of Asia truly is. Indian’s are often relegated as the “smart STEM kids” who come from a country where people defecate in the streets. Everyone at this point is familiar with the notions people from the Middle East have to face: they’re misogynistic suicidal zealots. Growing up, I was constantly met with remarks by my peers and classmates that fortified these notions: “Hey, you’re good at math right, can you help me with my homework?” and “Oh you’re Asian? Can you do a jump kick?” were some of the most common. While I never took offense to them, they definitely affected how I approached certain topics and carried myself around others.

Granted, Asians have slowly but surely begun dismantling these social perceptions, with the success of names like Yao Ming, Jeremy Lin, Naomi Osaka, Ming-Na Wen and Hasan Minhaj in non-stereotypical fields, the gradual acceptance of other areas of study in Asian families besides STEM and the overall progression of society towards a more inclusive mindset.

“Fortunately, I have never felt like I’ve been unwanted to where I would have to assume it was because of my race. I wouldn’t say I’m regarded as unathletic because I’m pretty good at soccer, although to be fair, I don’t look like the stereotypical oriental Asian,” senior Fretz Barcelona said.

However, while these stereotypes have slowly begun to fade from the public consciousness, there are still terms and remarks that remain very pervasive and damaging despite efforts to move past them. Even at WJ, these comments and insults are commonplace among the student population. While we disparage the usage of the N-word and stereotypes relating to immigration, physical attributes and diet for other cultures, it feels like there’s no filter for those targeted to Asians.

“On social media, I see a lot of non-Asians making derogatory statements towards people of Asian descent. “Dog eaters,” “chinks” and “go back to China” are all things I’ve seen said towards other people,” a Korean-American student (who wishes to remain anonymous) said.

The concerns of the Asian community are often disregarded by even other minority groups. The culprit seems to be the case of the model minority myth. While the myth poses a myriad of problems ranging from removing individualism and diversity to justifying the upholding of institutional racism, it also creates the issue of ignoring racism towards Asians and perpetuating the image of the outsider group. By placing Asian Americans and immigrants on this pedestal of supposed superiority that other minorities should follow, it separates Asians from other demographics and creates a sentiment of distrust and jealousy.

“I’ve also seen a lot of POC dismiss the increasing hatred towards Asians in the United States because they hold a false perception that Asians are essentially white people in terms of privilege due to the model minority myth,” the Korean-American student said.

Last November, Asians were lumped together with white students in a Washington state school district’s equity report, as their academic success didn’t fit North Thurston Public Schools agenda. In the eyes of NTPS, because Asians don’t suffer from “persistent opportunity gaps,” they are no longer considered a minority by that definition. It is these types of generalizations that further ostracize the Asian community from other minority groups, and create even more conflict by inferring that Asians are superior to other groups. Beyond that, it also ignores the struggles of Asian students who don’t fall into the preconceived image of the “smart Asian.”

This type of anti-Asian sentiment is found everywhere: from day-to-day interactions to even community meetings. In a published recording of a committee hearing in Brooklyn that took place in May of 2019, a woman came up to testify on the behalf of high-achieving Black and Hispanic students by lambasting the inherent culture of “cheating” in Asia. Not only did she bring up statistics from solely China and generalize the entire continent, but she also postulated that these “new immigrants” were purposefully bringing that harmful culture here. Does this rhetoric sound familiar?

Until recently, Asians haven’t been the source of continued targeted oppression in America for quite some time. The Chinese Exclusion Act and internment of Japanese immigrants and Americans both happened decades ago, granted this doesn’t mean its effects aren’t still visible now. One of the most relevant yet also unknown cases of anti-Asian violence, the murder of Vincent Chin, happened in 1982. The racially motivated harassment and abuse that led to the suicides of servicemen Danny Chen and Henry Lew occurred in 2011. In comparison to the constant struggle for equality that the Black community has been fighting for, the discrimination and paranoia over Muslim people and the maltreatment of Hispanic immigrants, to some, the state of the Asian citizen may seem to be in a much better spot. Yet, it’s the little things over time that have counted; the microaggressions and stereotypes that’ve slowly built into a great wall that barrs Asians from outside help, and confines them within this social construct of what people think they should be.

Despite this, for all of my talk about challenging stereotypes and preconceived notions, some of them are right: Asians aren’t able to fight for fair treatment. We brown nose and remain quiet and content with the status quo. We’re divided by the color of our skin and the inherited hatred from our predecessors that we should have no business bearing. There’s a term in the professional world called the “bamboo ceiling,” the notion that because employers recognize that Asian workers tend to not complain as often and be assertive due to their culture, they’re able to keep them at entry-level positions for years, if not decades, and continue to pile on more work without increasing their pay.

Even after years of effort and attempts to break barriers between Asians and everyone else; to overcome the hurdles that our culture and ethnicity pose for us, nothing has really changed. This is the reality with which many Asian youths soon find themselves confronted.

Seeing through the slits; is there a lack of Asian representation at WJ?

The New Yorker has a very poignant and relevant article titled “The Stories We Tell, And Don’t Tell, About Asian-American Lives” and I’d like to quote the opening paragraph: “There were many Asian-American students at Columbia, but Eng and Han had noticed that these students often spoke, in the classroom and at the clinic, of feeling invisible, as if their inner lives were of little concern to those outside their immediate community.”

I’d like to preface this by saying that I was never one to really care about representation, at least to the lengths that most discussions regarding it nowadays go to. Perhaps it stems from the fact that I truly didn’t have any Asian idols to look up to in my youth, so the idea of representation was an unneeded stranger, and thus I was never hungry for it growing up.

Of the various responses I’ve received from Asian students here at WJ, there’s a shared theme in a few: one of isolation. One of the major topics of contention among WJ’s Asian student body are the various cultural assemblies WJ puts on. They’re a chance for the student body to recognize and celebrate the various cultures we host at our high school. At least, that’s what they’re supposed to be.

“Overall, the Walter Johnson student community has treated me with minimal respect. From …attempting to cancel cultural assemblies, it has been made very clear to the Walter Johnson Asian community that they are not worth themselves as students but rather as an accessory to parade around,” senior Nicole Kang said.

Kang, who was an active participant in the Asian Cultural Assembly in her freshman year and later the host of the assembly in her sophomore year, is one among many students who find that the school’s cultural assemblies solely exist to appease minorities; an act that is clearly failing for some.

“In the past three years, Walter Johnson staff have tried every tactic in the book to have [cultural assemblies] canceled or shortened,” Kang added, “We were requested to be mindful of our time and heavily alter the content of our assemblies in order to fit that allotted time slot, which definitely is unfair considering that this mindfulness was never asked of those who run the pep rallies, which literally take up more time. Canceling assemblies were definitely suggested not too long ago in order to have a ‘less disruptive learning schedule.’”

I have to clarify that the majority of responses, as curt and short as they were, found that our school’s environment is relatively welcoming and inclusive, even though many of those responses noted that they were often the butt of racial jokes and stereotypes, so there’s clearly a disconnect between how some Asian students feel compared to others.

“[I’ve been treated] like a normal person, I see no discrepancies in treatment between white and Asian people,” sophomore Ziyi Lu said.

An interesting thing of note is that while those who either clearly “looked the part” or openly shared aspects of Asian culture, like K-pop or anime, felt more ostracized, those who admitted that they didn’t match with the stereotypes had a much more positive experience.

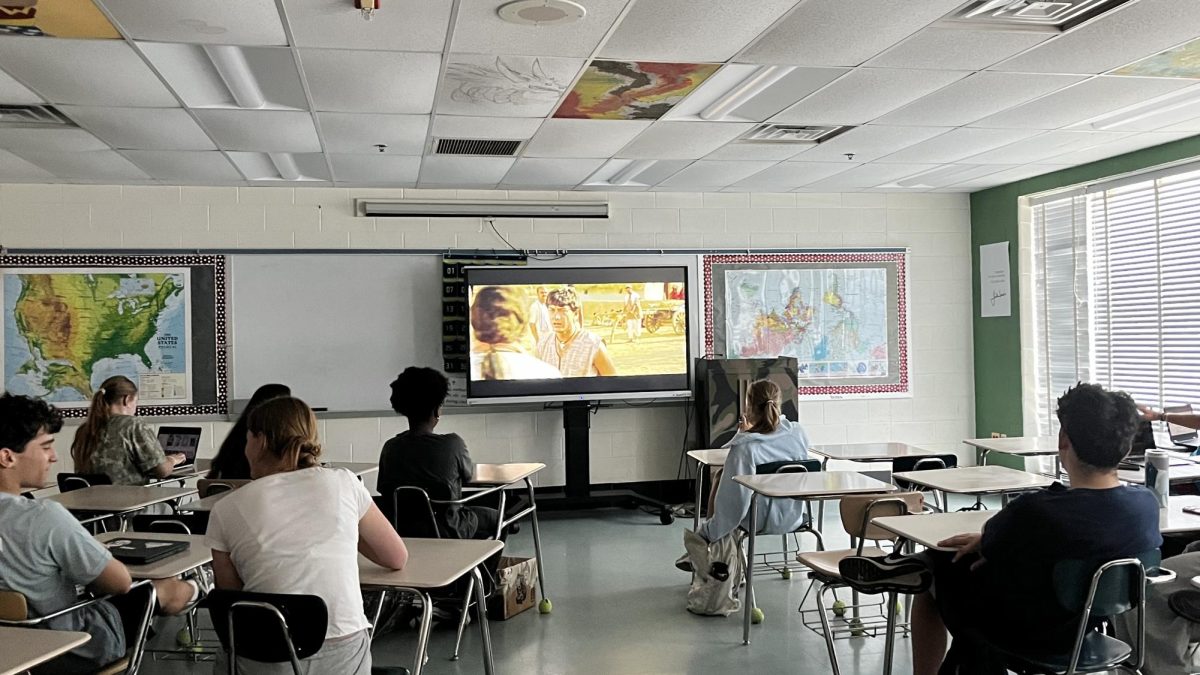

All things considered, while the general student body seems to be relatively accepting of Asian students superficially, both administration and classmates seem to struggle with the cultural side of things. Heritage and culture assemblies are clearly there to pacify the minority population, and more often than not, due to the lack of matching effort put in by the administration, often fall short and serve more as a mockery than anything. If more were to be done in allowing minority groups, not just Asians, to share their culture and make it more acceptable, the resulting effect on the student body would be far more positive. A major reason why non-Asian students often ridicule things like K-pop, anime and Asian fashion is that, like many other oddities, they haven’t been exposed to it enough.

The COVID-19 Climate:

We can’t discuss the current Asian/Asian American experience without addressing the COVID-19 pandemic. Not since World War II have Asians been targeted, ostracized and abused to this extent by not just the government, but also the citizens of the United States. From assaulting elderly Chinese women on the street, lighting people on fire, calling the disease the “China Virus” or “Kung Flu” to spewing hateful, undeserved vitriol towards Asians, America has once again shown how ugly and bigotted it can be to just about anyone. There is plenty of documented information online describing these occurrences, so I’ll instead focus on what it’s been like for the Asian students at WJ:

“When the pandemic had first started, I was at CVS with my mom. I sneezed and she offered me a tissue…when I sneezed a whole bunch of white women looked at me with disgust, whispered and then quickly left the CVS,” senior Kylie Chreky said. “Another time when my mom and I were at IKEA a white woman was being really rude to my mom and the cashier, and this woman kept emphasizing that she didn’t want her items to be mixed with my mom’s. And so my mom said that our items are very different so she was sure that the cashier wouldn’t mix them up. And the woman said to my mom, ‘Shut up China lady, go back to China and take the virus with you.’ And all my mom said was, ‘I’m actually Korean.’”

Even in a place like Bethesda, where the population leans heavily towards being liberal and identifying as Democrats, you still hear rhetoric that you’d expect from more insular, racially-exclusive areas. Some students don’t even need to experience these types of interactions to feel out of place; the social and political climate that has seized the nation since the beginning of last year has created an environment where just being outside feels unwelcoming.

“In the early stages of COVID, I would get weird glances going to places such as the grocery store. After videos of Asian discrimination (due to the pandemic) surfaced, for the first time, I actually felt worried to go out,” senior Evelyn Pham said.

It’s imperative to understand how damaging this sort of behavior is. Associating Black people with Ebola and crime, or telling Latino Americans and immigrants to “go back to their country” is met with immediate resistance and outcry, so why not the same for Asian people with COVID-19? I’m not saying that people haven’t been speaking out against it; they have, but the overall direction of the public consciousness doesn’t seem to be moving where it should be and as fast as it needs to.

Even after 2647 words, there’s still much to be said. From tackling the issue of who “qualifies” as Asian, as there are many who feel that those from the Middle East and even India don’t fall under this classification, to the apparent lack of care for the developing political and cultural state of the Asian continent, there’s so much more work to be done and discourse to be had.

I’ve held off on writing the conclusion to this article for days, not just because I’m a lazy procrastinating bastard, but because I felt that something monumental to the Asian cause was about to happen after years of inaction. After all, with every receding of the tides comes a wave.

I was right.

Protests have erupted in states like New York and California demanding an end to targeted Asian violence. There’s been a surge in social media activity pertaining to tragedies happening in Asia like the Myanmar coup and mistreatment of minorities like the Uighurs and Rohingya. Jeremy Lin, who returned to the NBA after years of abuse both here in the U.S and China, has spoken up about racism on the G-League court. It seems the Asian population in America has finally reunited after decades of division. And I would not simply just dream of an America that does not judge future generations of Asians and Asian Americans through the thin slits provided by racism and stereotypes; its judgment impaired by the great walls of racial division and mistrust, because I know that those alive today will make that future a reality.

Writing this article — even just thinking about it, has been a struggle, to say the least. There is conflict in this yellow soul of mine: “Am I the right person to be writing this?” Anybody that knows me can declare without hesitation that I make light of my Asian identity almost every day. From saying that my fellow editor’s bunny looks absolutely scrumptious to jesting that I cannot see because my eyes are too small, I perpetuate and partake in the same harmful behavior I’ve since outlined. I said earlier that I’ve never really been one to care for representation; that while I empathize with the ever-present struggle to change the flawed image of what it means to be Asian, I’ve never really taken meaningful action on behalf of it.

This is me doing so.