In essence, popularity is an illusory concept. It’s an idea ingrained into our minds by movies, TV shows, books and other media targeting our demographic, but it is often difficult to directly identify. No two definitions of popularity are the same; in a given school, it’s likely each student would label a different cluster of people as “popular.” Even still, the idea of social status feels relevant to many teenagers’ personal lives. That is, it did.

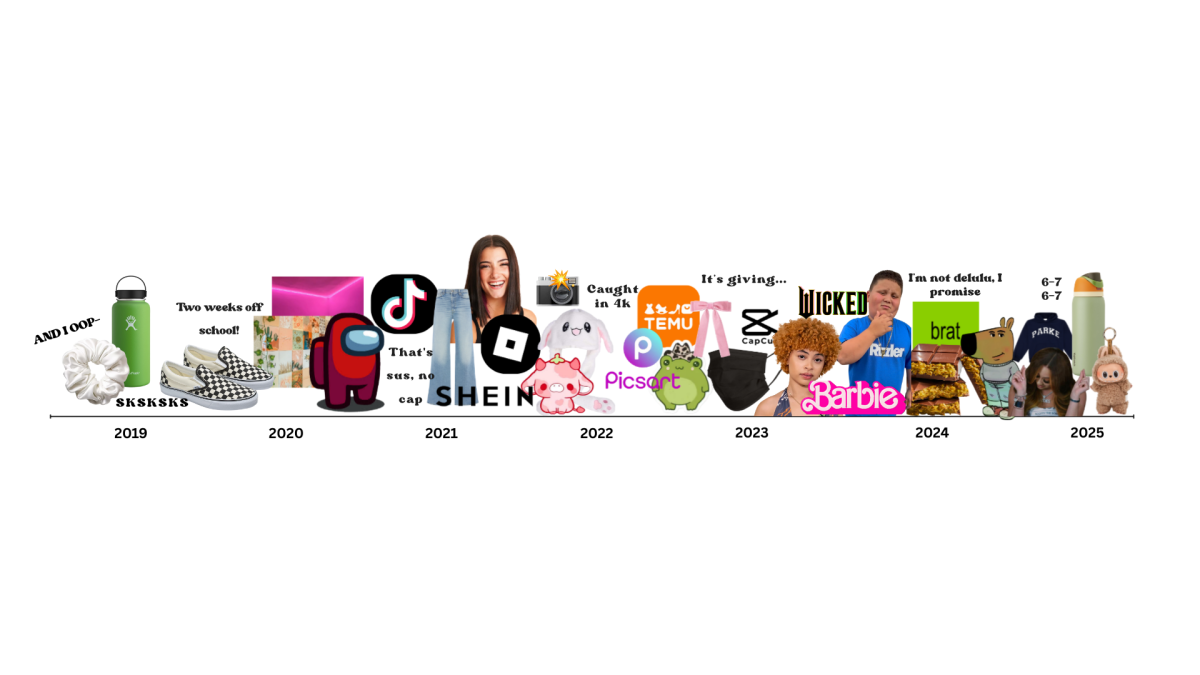

Reputation in high school has almost always been dependent on how you present yourself, what you do over the weekend, how many people you’ve dated and whether or not the general public is fond of you. (There is the exception of those who are “popular” for more notorious reasons, such as the judgemental squad in “Mean Girls”). Consider movies like “Grease,” “The DUFF,” “Booksmart,” “Can’t Buy Me Love” or any other cliched film focused on the clout of high schoolers. Although we don’t operate on a script, these social pressures are still a burden. There’s pressure to date, wear the most fashionable and mainstream attire, attend social gatherings, climb the social ladder and amass a liking — literal or virtual — from your peers. That is, there used to be.

You can see the pattern. These once heavy social burdens dissipated with the emergence of a pandemic, one that discourages close contact and physical gathering. Instead of being envied, high schoolers who choose to party are now called out for their lack of a conscience. Friend groups are now exclusive bubbles, as expanding a social circle exposes all members to the threat of illness. Identifying a social hierarchy is impossible when groups are isolated from one another. We are on an even plane — literally.

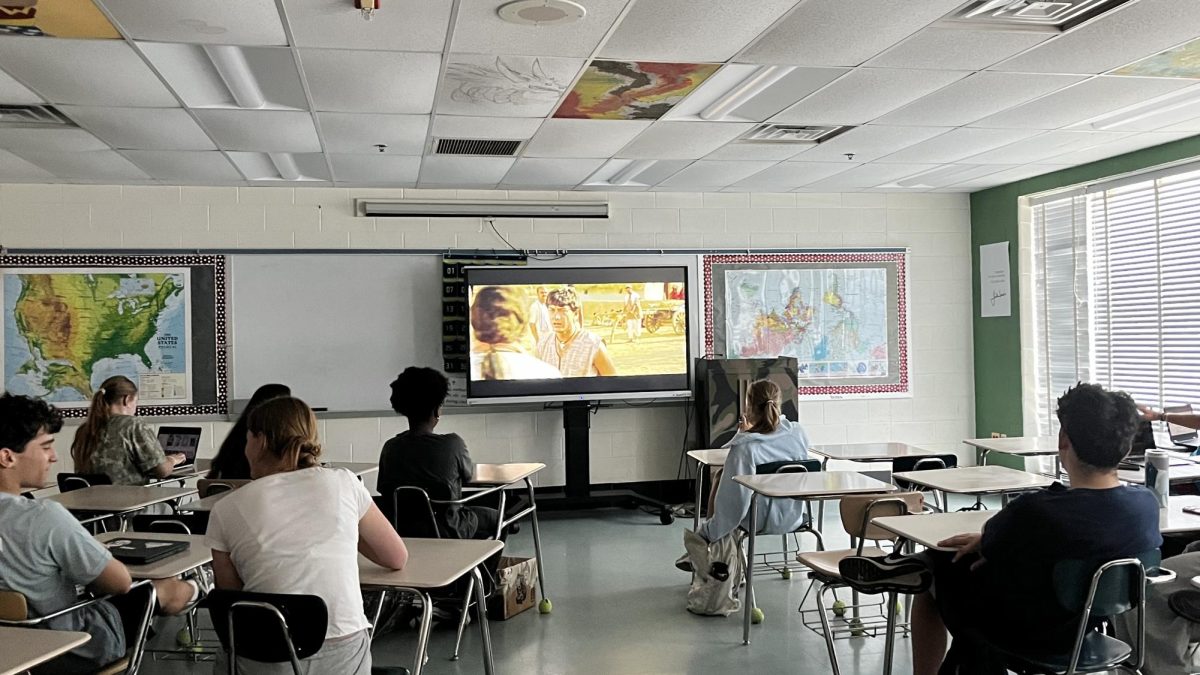

In our Zoom classes, the less-dimensional version of our former classes, every person is framed in a single square and separated from other classmates by a virtual border. Our “locations” in the classrooms are more or less random — with the exception of shifts due to fluctuations in volume. For the most part, breakout rooms are computer-generated as well, leaving no room for friendships to influence group makeup.

Therein lies an additional twist: social relations have little to no effect on the class dynamic. It is virtually (get it) impossible to determine how many friends a student has based on how they act in class, unless a student so bravely chooses to disrupt the lesson by interacting with their buddy in front of 30 other frames. There’s no more whispering to a desk partner, leaving class with a significant other or huddling in a friend group to complete a project.

In addition to being framed in a square, many students are practically invisible. Except the new invisible is still viewable: a black screen with a name in white font. It is unknown what the hidden students look like, much less what they are wearing or how their hair looks or what makeup is applied on their face. For those who do turn on their cameras, no more than an eighth of their bodies are shown. Since the dawn of Zoom school, outfits have gone extinct. Wardrobes contribute nothing to one’s status or reputation. But the pandemic has seen a rise in style-based experimentation, as young people alter the color of their hair and allow their wardrobe to deviate from the norm. This is because of the surplus of free time, but also the format of school.

And what to say about the other element of popularity: what students do over the weekend? Fortunately, or unfortunately, we have social media to document every second of our waking lives, including those endured during school hours. But documenting large gatherings or get-togethers no longer reaps envy- it reaps distrust and disdain. At our school, maskless gatherings to mimic Homecoming resulted in a spew of outrage in the community and on Twitter. Unless people are completely oblivious of more concerned citizens’ reactions, they will likely avoid broadcasting their gatherings — if they choose to gather at all.

Even if popularity is somewhat of an illusion, there were still defining steps to climbing the social ladder. With the pandemic, not only have some of the steps been taken away, but the ladder itself dissolved. Yet, the dissipation of a social hierarchy was far more gradual than many of our other losses. Our new standard is relative isolation or a small circle of a few friends. Living in social excess — the former image of popularity — is an act of danger and recklessness. With these current expectations, social reputation holds no weight in high school. Imagine attempting to produce “Mean Girls” amid a pandemic. How could it be done?

It is inevitable that the pandemic will eventually lose its grip over our minds and bodies. The big question, however, is whether our new outlook will allow social fluidity, as the barriers that once separated groups were shattered with the transition to online learning. Have our lives changed indefinitely or is this just the temporary death of popularity?