Believe it or not, teachers weren’t always teachers. Many of them held varying jobs and careers and lived wildly different lives until their paths eventually led them to education, enriching their teaching careers with their varying skills and experiences.

A trial run with law

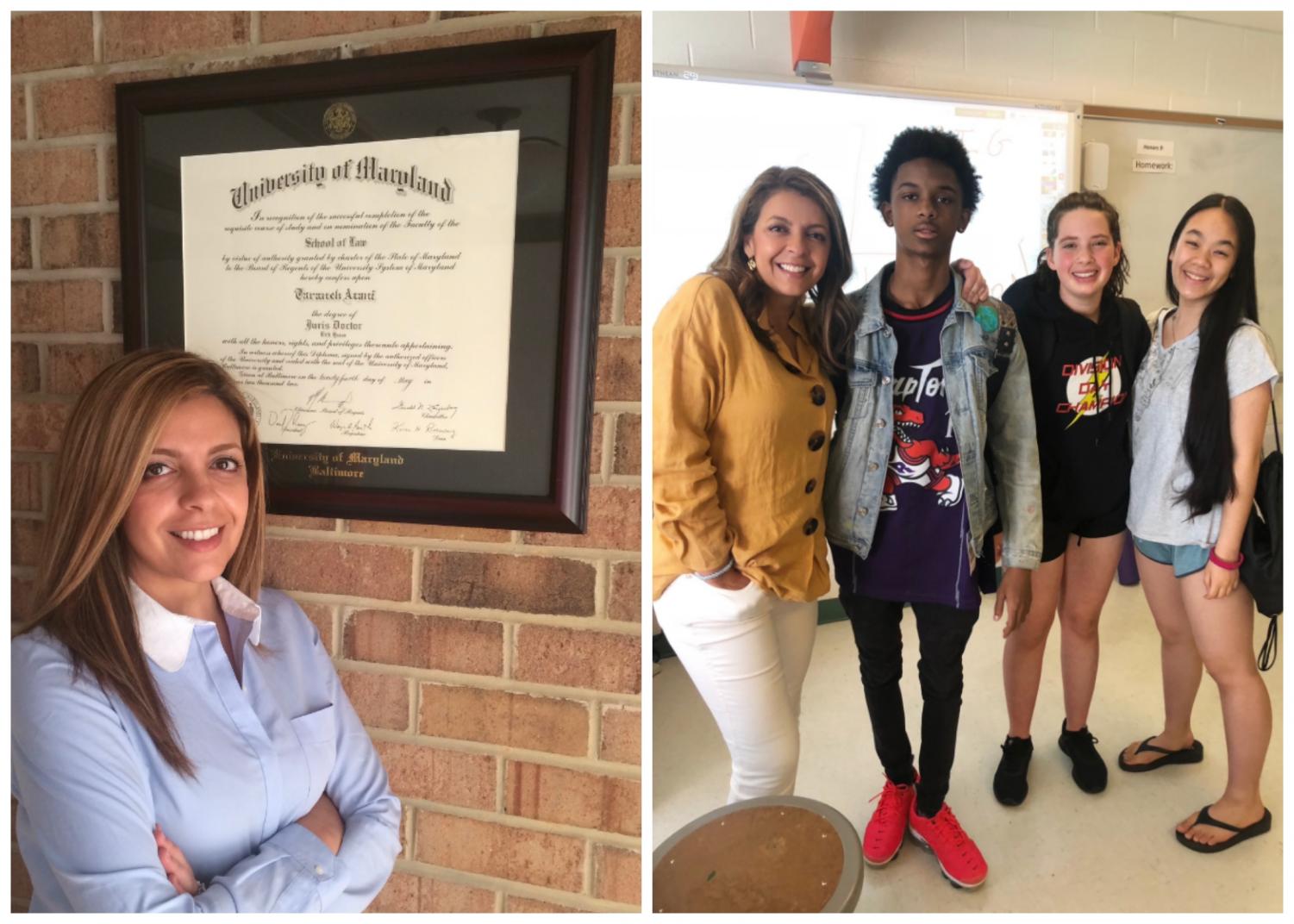

Taraneh Azani has been an Hon. English 9 teacher at WJ for three years, having worked at various high schools and middle schools in Montgomery County. In her current position, she teaches new WJ students coming in from middle school about higher-level narrative and argumentative writing, literary analysis and written communication, and — being that 9th grade English is one of the first courses that students take in high school — bridges the educational gap between middle school and high school.

She has not always worked with adolescents in this side of the picture, though. Before teaching, Azani practiced law. She had pursued criminology and criminal justice in her undergraduate years at the University of Maryland, College Park, then found herself at a year-long stint working paperwork at a corporate law firm in Europe soon after graduation.

“What was great about that job was that… it helped me realize that wasn’t the area of law I was interested in pursuing because it involved a lot of paper-pushing, whereas I’m kind of a people person, so… after my one-year stint at that law firm, I realized that I wanted to be in litigation. I wanted to be in the courtroom handling cases,” Azani said.

Finding oratory as more natural to her, Azani then went to law school and landed a job as a juvenile prosecutor.

“I loved being in the courtroom, I loved advocating on behalf of my victims, interviewing witnesses and prepping for trials, but it was also sad. A lot of the defendants were young and didn’t have role models… while I was good at my job, it wasn’t fulfilling for me because I didn’t feel good locking kids up,” Azani said.

After some time of working in litigation, Azani left the practice of law and took on a teaching job. From there, she transferred through various middle and high schools until she finally found herself at WJ.

“I thought that, maybe… I could get to kids before they turned to a life of crime… it’s a better lifestyle for me, right now, and [teaching] is a more rewarding profession,” Azani said.

She is open to returning to law sometime in the future but is satisfied with her current teaching position. Concerning teaching, Azani is also interested in teaching law at WJ or helping out with its Mock Trial team.

Had she not moved into the legal profession, Azani may have opted to go to medical school as she was also interested in pursuing medicine.

Building muscle… with science!

At the forefront of medical and biomedical sciences in the US are the National Institutes of Health, headquartered at Bethesda, Maryland. This is where biology teacher Joan McDermott used to work.

“I am a molecular developmental biologist, and my interest is how are gene actions regulated so that each person goes from a single [fertilized cell] to an entire organism. In the course of my time and research, I’ve worked in six different labs. The last place I was working was at the NIDDK at NIH’s campus, doing a postdoc,” McDermott said.

In her last research project at NIH before moving to the teaching sector, McDermott — then a biomedical researcher — worked with the C. elegans nematode and raised them in agar dishes, studying and experimenting on the biological mechanisms that underlaid muscle formation in the worms.

Having earned her PhD in molecular biology, McDermott worked as a laboratory scientist before moving into teaching at the high school level. Throughout her scientific career, McDermott was exposed to various teaching opportunities; while pursuing her doctorate, she served as a teaching assistant to many undergraduate classes and throughout her time at NIH, she used her position to help teach budding researchers the ins-and-outs of scientific research.

“While I was doing graduate work, I discovered that I actually really like teaching. My overall plan was to work at a small college, doing research and teaching. It’s actually an incredibly difficult job… and I started thinking about teaching [in] high school,” McDermott said.

Since high school, McDermott has personally been worried about global warming. A big motivator that led to her move into teaching at that level was that she wanted to help teenagers and students learn about the issues and world-spanning consequences of global warming.

Currently, McDermott teaches honors biology and molecular biology at WJ. Like Azani, McDermott is open to returning to her former career in the future.

“I don’t plan to keep teaching, actually; I plan to retire. It’s a young person’s game, and I’ve reached retirement age with MCPS… I would very much enjoy it if I had the opportunity, even part-time or as a volunteer, to work in a lab again,” McDermott said.

To bee or not to bee?

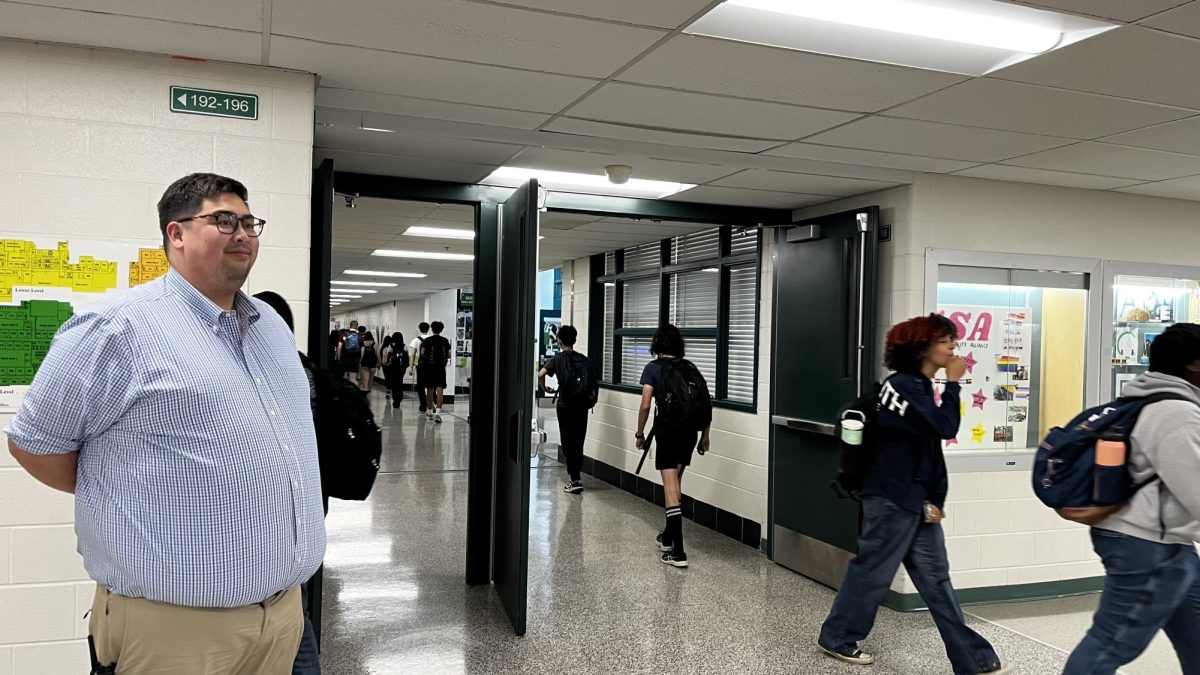

On the opposite end of the biological sciences spectrum is environmental science teacher Brock Eastman. While teaching his own sections, Eastman also works with the biology department as a whole to create available resources such as worksheets, student labs and lecture presentations.

“[Resource creation] is a huge part of it, that’s a lot of stuff the kids don’t see. Of course, there’s the stuff you do see, like the front-facing teaching, but all the stuff you don’t see… you don’t see the grading and you don’t see the meetings, it’s all over the place, there’s so much involved with this. From the days we start professional week all the way to the summer, you’re on call the whole time,” Eastman said.

Throughout his career, Eastman worked in both animal research and conservation.

Even in college, he explored his passionate interests in environmental and animal science. As a sophomore in college, Eastman worked as an animal technician at an environmental consulting company.

“It’s a fancy way to say that I lived out of my Subaru for the summer in forests in West Virginia catching bats,” Eastman said.

As an animal technician, he helped locate bats through radio telemetry to catch them (temporarily and harmlessly) and take their data for genetic studies. His work also helped shut down government-funded fracking sites to help save endangered bats’ natural habitats. After graduating college with a zoology degree, Eastman moved into an internship position at the Lubee Bat Conservancy, as both a bat keeper and general assistant.

After that position, he landed a job as a safari driver at Disney’s Animal Kingdom Theme Park, transferring into the animal keeping department there only a few months later. Eastman speaks on behalf of zoos and animal conservatories throughout the world, defending the practices of animal conservation.

“There is such a stigma around zoos, which is so strange because it’s this society that’s very against the idea of zoos existing, and we’re also equally passionate about conservation — or we say we are, yet we’re losing habitat at a rate faster than we ever have… They stopped orca breeding problems at SeaWorld, and then I see all these reports of ‘The rate of orca births [is] dropping dramatically; we don’t have enough orcas’… It gets to this point where you’re like, there’s nowhere left for them to live; there’s so few of them. We can keep the species alive in captivity. There’s a function beyond just having a theme park,” Eastman said.

Especially under Disney, Eastman sheds light on the strict conservationist practices of zoos intended to preserve the animals’ natural lives to the most feasible extent possible.

“Disney’s really — and I know, it’s hard to put this kind human face on a mega-corporation; you have to trust me ‘cause I’m in it — serious about animal welfare. Most animals [at Animal Kingdom] do not receive contact with people because [Disney is] so serious about being non-interventionist with [the animals’] life to the degree we can in captivity,” Eastman said.

Throughout his time in animal welfare and his days as an animal technician in college to his position as an animal keeper at Disney, Eastman took on many education-related responsibilities concerning conservation outreach, from going to public schools for animal presentation programs to showcasing park animals for guest education.

While at Animal Kingdom, Eastman took on a graduate program in partnership with MCPS, finding himself fully enmeshed in the world of education and, soon after, becoming a biology teacher at WJ. However, he has not completely left the field of animal conservation; he still holds his position at Animal Kingdom and has often spent summers and spring breaks working there.

“I don’t think [I’ll go back full-time in animal conservation]. I like teaching… I would like to keep a foot in that world as long as I possibly can, though; I think it adds a lot of authenticity to my teaching and to just me as a person, too,” Eastman said.