MCPS is often criticized for its grade inflation, with the semester grade policy and the 50% rule at the forefront of this issue. As students, we don’t bat an eye to these types of policies unless they are drawn into question, in which case we will defend them. But what has become much more noticeable from a student perspective is inconsistency in teacher grading policies, which in some instances acts as a counteracting force to the aforesaid policies that we often take for granted.

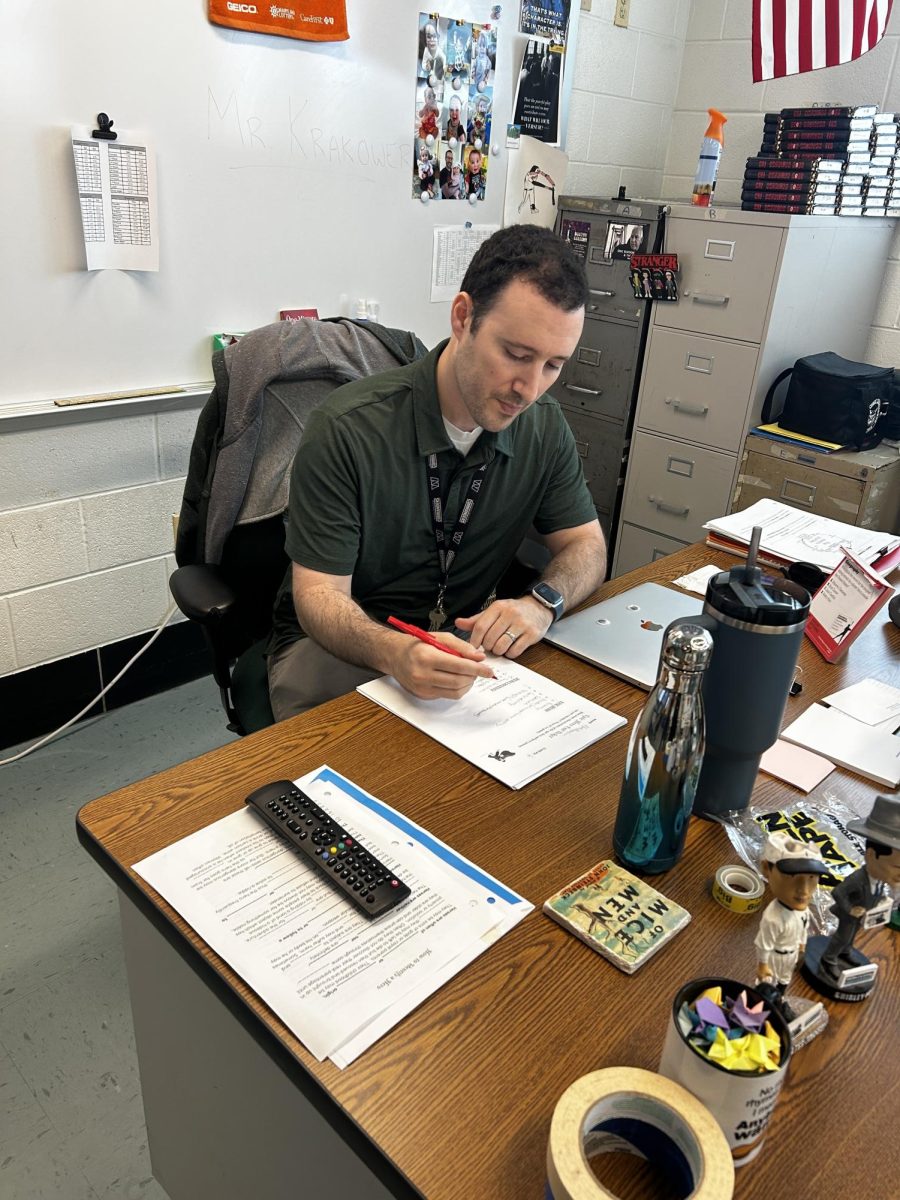

There is often a high level of variability when it comes to grading styles and policies of teachers. What one teacher deems as a “practice/prep” worthy assignment, another teacher may see as worthy of “all task” points. While slight differences like the one described seem trivial, they can have deeper implications when those differences involve how a teacher grades their students’ work, especially in classes where grading is more subjective than objective – take an English class for example. What is generally regarded as ‘A’ level work in one teacher’s class may be a borderline ‘C’ level essay in another teacher’s class.

Leading into junior and senior year, when grades are of utmost importance for those pursuing a college education, students find themselves asking their counselors if they can switch out of a certain teacher’s class, given their reputation when it comes to grading.

While differences in grading may result in a student looking better or worse when presented to a group of college admissions officers, there is not much they can do about these circumstances, as most counselors won’t grant schedule changes solely based on teacher requests. Instead of fretting about the grading inconsistencies between teachers, students should embrace the challenge it presents. Given all of the aforementioned crutches, it’s good practice to adapt to the preferential differences and differing grading styles between teachers.

A hidden benefit of these harsher grading policies is that it forces students to slow down and pay more attention to the quality of their work. When students know an assignment will be assigned a practice/prep grade, otherwise known as a completion grade, it’s easy to do the bare minimum knowing that a teacher is obligated to give full credit for the given assignment.

On the other hand, there are some teachers who grade practice/prep assignments for accuracy, as if it were a quiz or test. Instead of receiving 10/10’s for lackluster work, students may be given a 7.87/10 on a homework assignment they spent five minutes rushing through, reinforcing the practice of diligently completing all forms of work, not just all task assignments. Of course, nobody wants all seven of their teachers to grade in this manner; but that’s usually never the case anyway, and it’s good to have a healthy mix of the two styles.

In a grades-driven school culture, where we often fall victim to the mindset of learning to get the grade, rather than learning out of interest, it is teachers like these who keep us honest, upholding the ever-so-elusive standard of “academic integrity.”