“Would someone like to answer the warm-up question on the board?”

A hush falls across the crowd. More often than not, nobody feels like answering whatever warm-up question the teacher has assigned for the day. It’s 7:47 a.m. The late bell rang two minutes ago, but a few students are still rolling into class with their caffeinated beverage of choice in hand. First period has begun, and so has another school day.

Teachers have a hard time getting students to participate and pay attention throughout the day, not just during the first period.

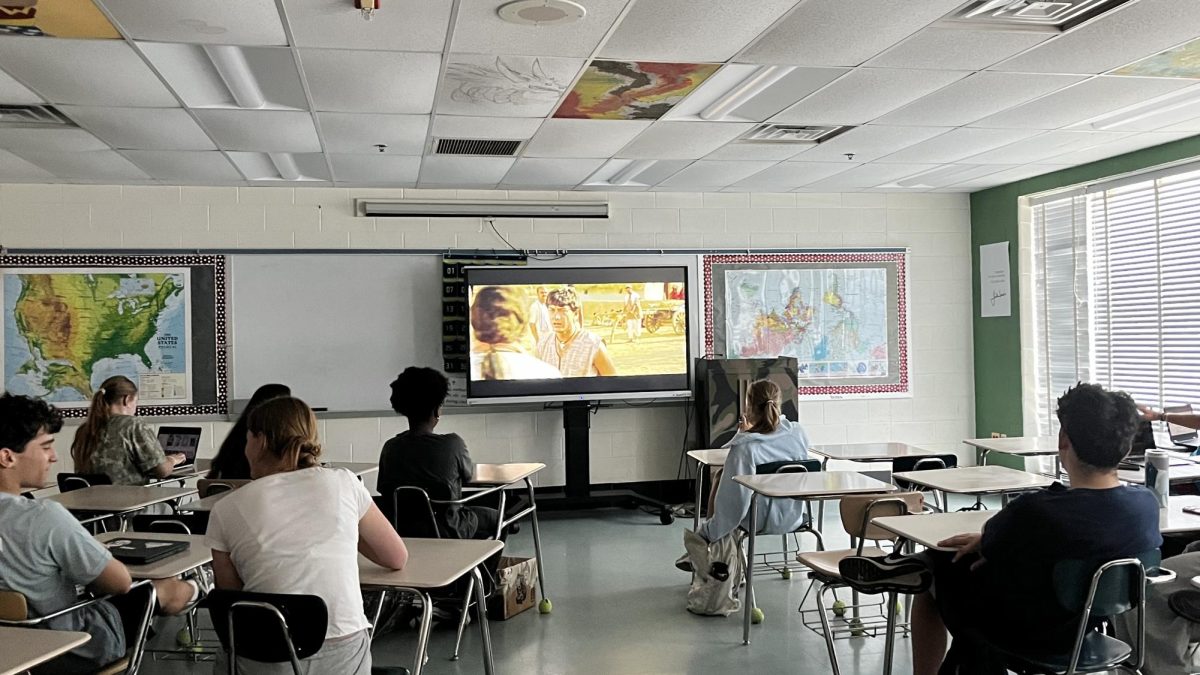

This conundrum can be handled in a couple ways: the teacher accepts the fact that students won’t willingly participate, and they structure their class around this deficiency, turning to a Google Slide presentation paired with a lecture. Or, they combat their students’ reluctance to participate and pay attention by running their class in a way that forces students to engage, whether they like it or not. I’ve had teachers who stick to one method or the other, and some who use a combination of both.

However, neither seems to be effective, which begs the question – what can be done to make class more engaging?

Student boredom in class comes from a few things other than just not enjoying the subject of the class. Monotony of every-day lecture is at the forefront of this issue, with every day seemingly a repeat of the day before. To switch up the tempo, teachers try facilitating graded discussions, where a student’s grade is dependent on their participation. There is often a set amount of times that a student needs to speak in order to get the grade they want. The problem with this sort of procedure is that there is usually a rush of students to answer questions at the beginning of the discussion, in order to fulfill the predetermined requirements. But as time goes by, the dialogue slowly comes to a halt, and most students sit back, having already spoken enough times to receive their desired grade.

A more natural way to conduct class would be to leave class open to dialogue, encouraging dialogue from multiple voices, without attaching a grade to it. In this manner, teachers can expect to hear from a handful of students, without posing the risk of a few students taking over the discussion just because they want to get their point across to get the grade.

This method is used in my Political Psychology and Behavior class, where we have a discussion based on a certain topic (example topic: was the insurrection of the capital an act of terrorism?), and a written reflection following the discussion. Those who participate numerous times during the discussion are not expected to have as thorough a reflection, while those who engage less are expected to have a more robust reflection. Either way, everyone has the opportunity to achieve their desired grade, whether they voice their opinions often or not.

In this manner, all students are held accountable to engage in the discussion, whether this engagement comes through verbal communication or by maintaining attentiveness to the content of discourse. Graded discussions are necessary to disrupt the flow of everyday classes, a break from mundane lectures and note-taking, and sometimes a substitute for a test or quiz; but they should be conducted through a system that is conducive to a classroom of 30 students.