In January of 2016, Texas based company Energy Transfer was given approval from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to begin construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). Originally proposed as an efficient method of transporting crude oil from fields in Wyoming and North Dakota towards markets in Iowa and Illinois by the end of the year, the pipeline has since become a massive environmentalist issue, largely in part due to the Standing Rock Sioux tribe’s involvement in its opposition.

Tribe members were furious at the pipeline’s proposed construction route, which was planned to pass near their reservation land, sacred burial grounds and under the Missouri River. As the pipeline passed through its final stages of building confirmation, fears of polluted water and indignancy at the disrespect of Native American’s welfare had already fueled rage in the Sioux tribe. Starting in August, around 3,000 tribe members gathered at the construction site, rallying behind chants such as “Can’t drink oil, keep it in the soil!”

Romin Mirmotahari, a senior at Walter Johnson High School who dabbles in stock market investments, was faced with a particularly precarious decision back in early November. Having invested in Energy Transfer a few months prior to the pipeline’s construction confirmation, Mirmotahari knew exactly what to do once the pipeline became a certain project.

“As soon as I learned about the details, I immediately sold everything I had with Energy Transfer,” Mirmotahari said.

Ditching the investments, Mirmotahari explained he was certain that he had made a justified choice in the matter.

“The fact that they were routing a pipeline under a river and through sacred Native American lands alarmed me, and I decided that it was morally wrong to have any involvement in it,” Mirmotahari said.

Even though the pipeline’s construction was now well beyond public news in the oil industry, national coverage was still slow to react to the rising protests. But as the protestors’ numbers grew, so did Standing Rock’s police resistance, which reached violent proportions heading into late September. In one particular clash, 30 protesters were pepper sprayed and six were bitten by police dogs. The police were also beginning to uses riot control techniques such as rubber bullets and fire hoses in order to quell the protesters’ fury. Desperate for assistance, the police at Standing Rock eventually gained support from 11 other states in the country. Since the protests began, hundred of activists and Sioux tribe members have been detained or arrested.

As the weather turned colder and the conditions of the protesters became more dire, the Sioux tribe still refused to back down. Garnering public support from the likes of Leonardo DiCaprio, presidential candidate Jill Stein and over 450,000 people who signed a petition on Change.org, the DAPL was becoming even more controversial in scale.

On October 10, also the historic Indigenous People’s Day, Hollywood actress and activist Shailene Woodley took a stand against the pipeline, as she took part in Standing Rock’s protests. After an encounter with police forces, Woodley livestreamed to FaceBook the arrest of herself and dozens of fellow activists and tribe members who were arrested for trespassing. According to a statement made in TIME Magazine, Woodley, like many across the nation, was angered at the lack of coverage regarding the pipeline’s conflict.

“Treaties are broken. Land is stolen. Dams are built. Reservations are flooded. People are displaced. Yet we fail to notice. We fail to acknowledge. We fail to act,” Woodley said.

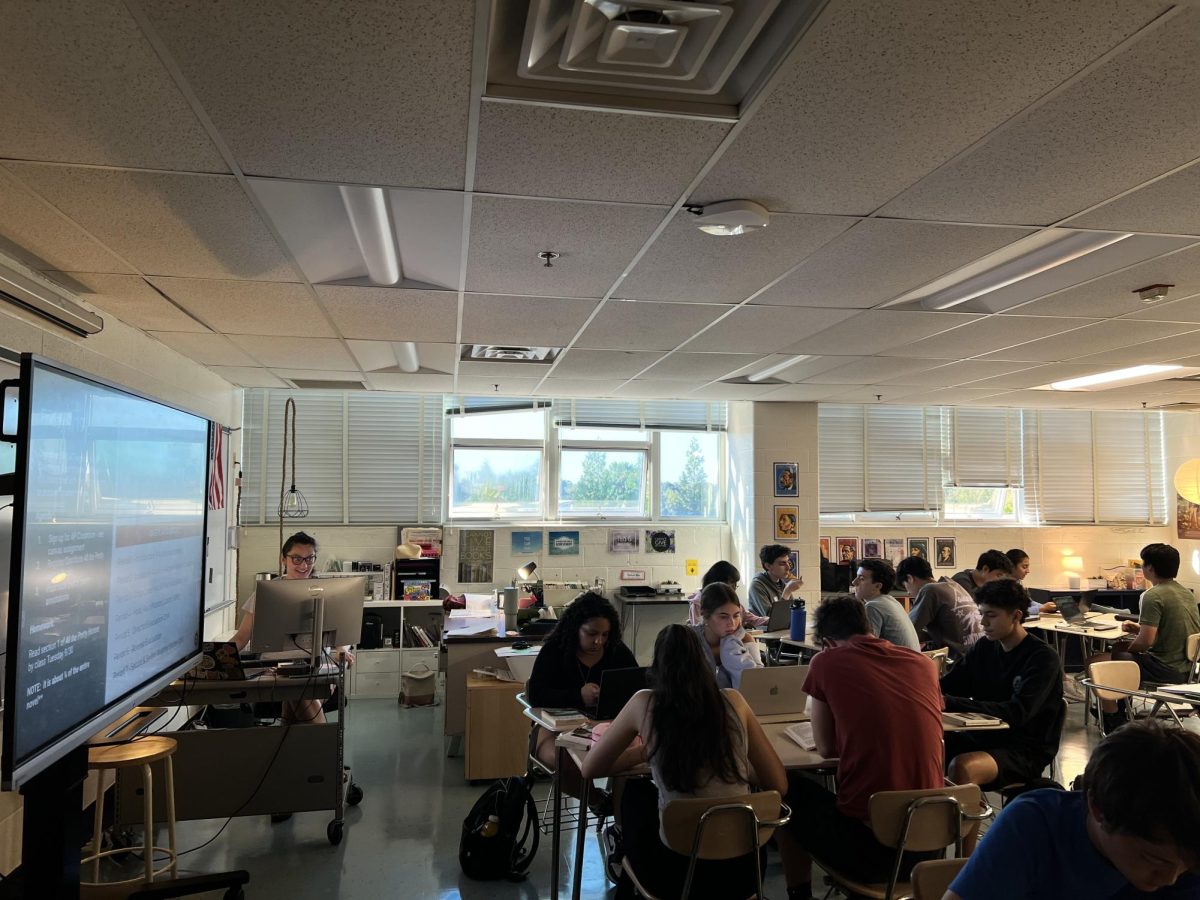

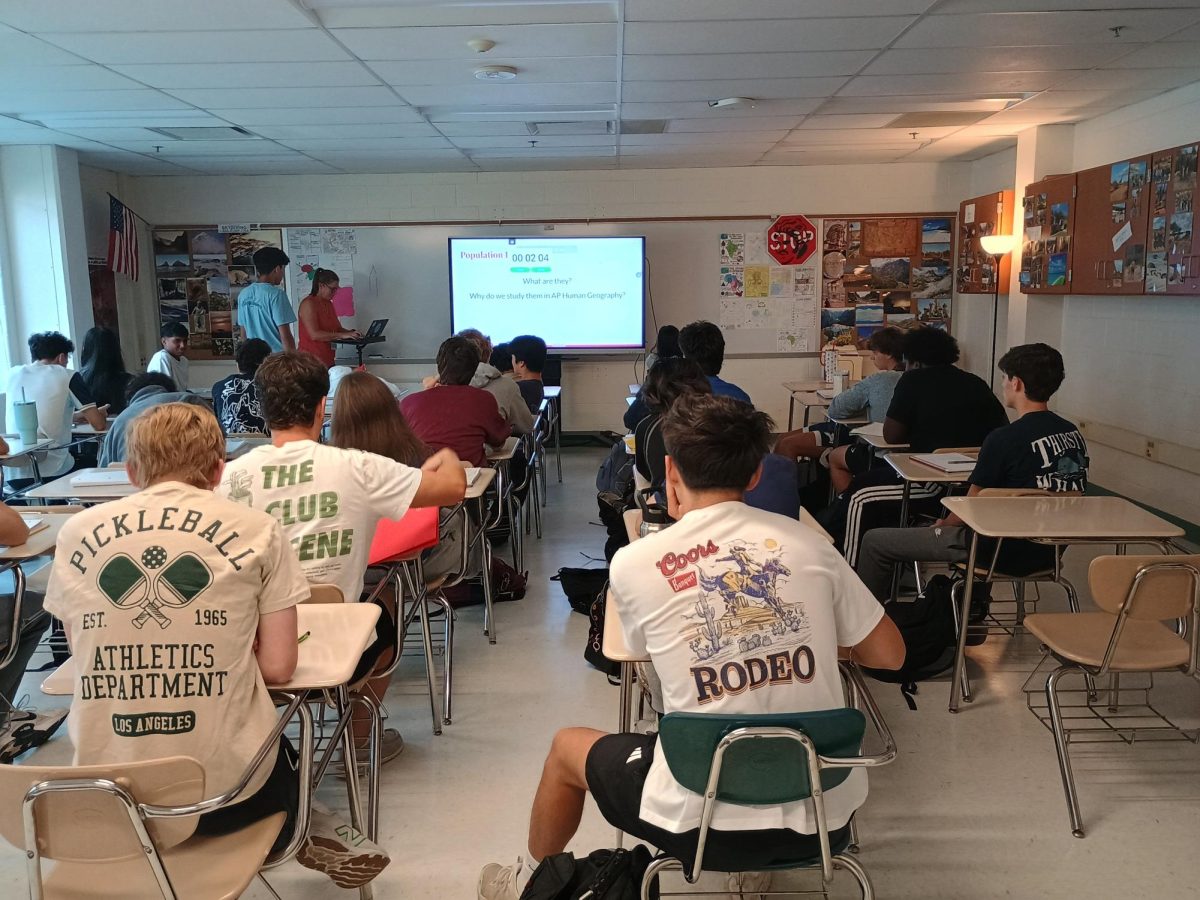

Just two weeks ago, WJ English teacher William Griffiths voiced his own concerns about the DAPL conflict. Combined with student efforts, Griffiths displayed a compilation of protest footage at Standing Rock in the halls of WJ.

Junior Livia Rappaport, who helped Griffiths edit the presented clips, is strongly against the pipeline’s construction and believes that the media’s coverage of the protests are not nearly as vast as they should be.

“My personal views were that the pipeline and the violence going on needed to be stopped. Our goal with showing the footage to students was to educate the students as to what was going on in standing rock, because it seemed to us like the news wasn’t doing a good enough job,” Rappaport said.

On Sunday, December 4, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reached a decision to halt the DAPL’s construction path through Standing Rock and under the Missouri. Though this is a massive victory for environmental activists and Native American tribes everywhere, there is still much to come in the DAPL debacle. The Standing Rock protesters are already bracing themselves through a bitter, blizzard-filled North Dakota winter, which has hospitalized nearly 300 protesters in just the last two weeks. Donald Trump’s election is also raising concerns, since he has personally invested in Energy Transfer in the past. This could mean any potential executive orders or policy changes from his administration could bring the pipeline back into construction.

Needless to say, an entire nation, divided between support of environmental activism and the backing of the U.S. energy industry, will be awaiting the DAPL’s finale.

Glenn Quagmire • Dec 19, 2016 at 7:10 pm

If the Indians were so upset about the pipeline, why did they not respond to multiple requests for input from the Army Corps of Engineers. Why did they not scream and holler about a pipeline already in the area when it was being built. Something tells me that White Man did not offer enough wampum. Ironically, the protestors want the pipeline moved from its current location (about 70 miles from a water intake) to a location about 2 miles from a railroad crossing which is how the oil will have to be transported if the pipeline is not built. And pipeline are a whole lot safer. Sorry to ruin your party with facts.