In September, the voices of friends and families harmonize in traditional new year songs and the scent of coffee fills the homes of Ethiopia. A month later, India comes to life as firecrackers and lamps illuminate the nighttime sky in celebration of the Diwali festival. In Russia, the smoke from bonfires and burning straw during Maslenitsa fade into the atmosphere. All of these traditions and cultures are brought to Walter Johnson by students of different ages and races, each with a unique story and background.

Tanvi Saindane

For 13 years, junior Tanvi Saindane lived in Pune, India, 200-300 kilometers from Mumbai. She relocated to America for her father’s job as an IT consultant.

“I was very nervous. I had moved before to the UK, but then [moving to the US] was not as easy as moving to the UK,” Saindane said.

Saindane and her family continue to keep their traditions, such as Diwali, one of the most popular festivals of India. It usually lasts five days and is celebrated between October and November.

“It’s also known as the festival of lights. It is celebrated because good defeated evil. We make different types of sweets, snacks, we wear new clothes and then we burst firecrackers,” Saindane said.

Traditional Indian foods, such as chicken masala and curries are well-known in America today. Although Saindane is a vegetarian, she still enjoys a variety of dishes that honor her culture.

“In my place, the most famous is puran poli. It’s like sweet bread made of jaggery. With the puran poli, we eat mango pulp,” Saindane said.

Aleksei Korotaev

Sophomore Aleksei Korotaev moved to the United States for his father’s work just three years ago, from Siberia, Russia, the coldest region of Asia.

“It’s very hard to live in Russia. The main problem is that any other job like [a] teacher, or maybe scientist, artist and so on — they are very low paid, and you don’t get opportunities there,” Korotaev said.

Relocating to America has brought new experiences for Korotaev, including stereotypes and assumptions. A common stereotype of Russians is that they keep bears as pets.

“That’s actually not true; there are almost no bears there, but I know [one from fact] where this stereotype came from. In the 19th, 18th century, when foreigner guests came to Russia, like in villages, there was some [rumors] that basically some guy came and just walked with this bear around the village,” Korotaev said.

A popular holiday in Russia is Maslenitsa or “butter week,” in English. Maslenitsa is an ancient Slavic religious holiday, in which Orthodox Christians would partake in secular activities before the Lent season. The holiday lasts one week and is the last week they are permitted to eat dairy products, such as milk and cheese, hence the name “butter week.”

“It’s like saying farewell [to the secular activities], but [what] people mostly do there right now, is they mostly bake cakes; they just talk and eat,” Korotaev said.

Nathania Dawit

After living in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia her entire life, freshman Nathania Dawit moved to the United States two months ago. Dawit’s first language is Amharic. She learned English at an international school in Ethiopia, where students began to learn English in kindergarten. It was difficult for Dawit to leave her country and family behind and start over in a new environment. Everything was different, from the culture to the school system.

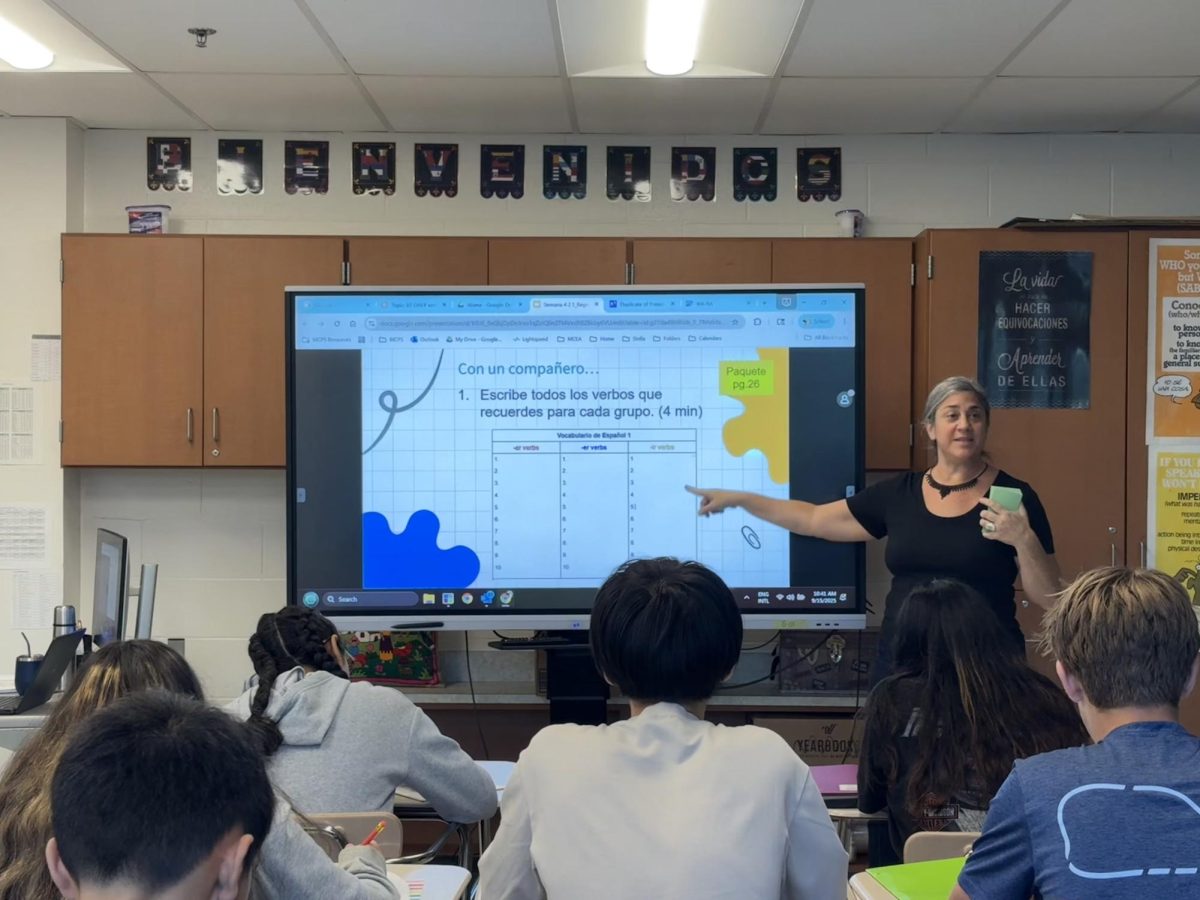

“In Ethiopia, we didn’t change rooms every period; the teachers are the one[s] that come to your class,” Dawit said.

Dawit celebrates the Ethiopian new year each September with her family and friends. Each year, they gather together to share meals and sing traditional songs.

“On new year, we cook traditional foods, make coffee (we call it buna) [and] we wear a traditional cloth called habesha kemis,” Dawit said.

During religious holidays and festivals, popular traditional foods are often served. One example is doro wot, which consists of chicken and boiled eggs, coated with a curry-like hot sauce. Dawit’s favorite dish is kitfo.

“It’s made from red meat mixed with butter and other spicy spices,” Dawit said.

From their food, to holidays, to native tongue, students keep their traditions alive at school, learning and sharing them with one another.

“After all, WJ’s diversity is what makes it a unique and an accepting institution for students from various background[s] and cultures,” Saindane said.